Research Summaries from the virtual Herons of Worldwide Conservation Concern Symposium, 2021

Introduction

The second in a series of symposia on Herons of the World was held as part of the 45th Anniversary Meeting of the Waterbird Society during 8-12 November 2021; the entire meeting was held virtually due to the outbreak of Covid-19. This second symposium was originally planned as part of the 15th Pan-African Ornithological Congress (PAOC-15) in Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe, in 2020 but it was postponed, repeatedly, due to Covid-19.

With the postponement of that Congress and Symposium, the Heron Specialist Group (HSG) felt it was necessary to organize a virtual Heron-event that would keep the momentum going from the planning for the African meeting. With at least three heron species of conservation concern in Africa and the many developments with the White-bellied Heron in Bhutan and India, we felt a symposium focused on Herons of Worldwide Conservation Concern would be appropriate, especially in a virtual format where researchers from around the world could contribute without leaving the confines of their home or place of research. Focusing on this group of herons would be an excellent way to draw attention to our most vulnerable species, highlight their plight and showcase the work being done on them as well as make a worldwide appeal for support for their work.

The IUCN (2022), identifies 13 heron species, worldwide, that are of conservation concern. The White-bellied Heron (Ardea insignis) is Critically Endangered and the most threatened heron species in the world. The Endangered species include: the Australasian Bittern (Botaurus poiciloptilus), the White-eared Night-heron (Oroanassa magnifica), the Madagascar Pond-heron (Ardeola idae), the Madagascar Heron (Ardea humbloti) and the Great White Heron (Ardea occidentalis). The Japanese Night-heron (Gorsachius goisagi), the Slaty Egret (Egretta vinaceigula), the Chinese Egret (Egretta eulophotes) and the Agami Heron (Agamia agami) are classified as Vulnerable, and the near Threatened species include: the Reddish Egret (Egretta rufescens), the Forest Bittern (Zonerodius heliosylus) and the Zigzag Heron (Zebrilus undulatus).

We tried to locate researchers for each of these species; we were only partially successful, finding researchers for 7 of the 13 species: the White-bellied Heron, Australasian Bittern, Madagascar Heron and Pond-heron, Slaty Egret, Agami Heron and Reddish Egret. These contributions originated from India-Bhutan (5), Africa, and South and North America (8) and one from Australia. We were unable to locate researchers for: the White-eared Night-heron, Japanese Night-heron, Chinese Egret, Forest Bittern and the Zigzag Heron. We are excited to note that five of the presentations reported on advances in the conservation of the White-bellied Heron, our most endangered heron.

As with our reporting on the first Herons of the World Symposium, we invited the presenters to submit full length papers of their work to either Waterbirds (the journal of the Waterbird Society) or to the HSG’s own journal, the Journal of Heron Biology and Conservation (JHBC). For those who preferred a less onerous format, we invited them to submit an extended abstract of their work for publication in JHBC. The goal of this exercise, as before, was to present a formal update, in the public domain, on the very important conservation work on these selected species.

Below are the extended abstracts from eight of the papers given at the symposium. One full length paper has already appeared in JHBC, four more full length papers are near final and a wrap-up paper (J. Kushlan) is in hand waiting for the outstanding papers to appear. Coincidently, a paper, on the Great White Heron appeared earlier in Volume 7. It was not part of the Symposium but its subject matter is directly relevant. These abstracts and full-length papers provide an important update on the status of more than half of the Herons of Worldwide Conservation Concern.

We extend our greatest appreciation to the researchers who contributed their work on these species of Herons of Worldwide Conservation Concern.

Saving the critically endangered White-bellied Heron (Ardea insignis) from extinction: two decades of conservation efforts and the way forward

The White-bellied Heron (Ardea insignis) is Critically Endangered and one of the rarest heron species in the world. Fewer than 60 individuals are confirmed to exist today, spanned over Bhutan, India, Myanmar and China within the extent of 165,000 km2 of the Himalayan freshwater ecosystems. However, active nests and breeding populations are only known from Bhutan and India. Since 2015, after the preparation of the conservation strategy and hosting of the first international conference for the species, range countries have been putting efforts to protect the fragmented populations and restore their habitats. In Bhutan, conservation started in 2003 and soon after the first active nest was discovered. It was the first active nest for the country and rediscovery for the world after more than seven decades of the previous record. Over the last two decades, we have monitored the population trend, distribution and habitat use, nest, and active breeding population and mapped major threats to the bird and their habitats. We conducted the annual population survey for the last 19 consecutive years and recorded an average of 23.7 ± 4.4 SD (n = 19) individuals/year. The average annual number of active nests (i.e., number of breeding pairs) found was 2.6 ± 1.4 SD per year (n = 50) with an average clutch size of 2.7 ± 1.4 SD (n = 28). The average hatching success of 1.9 ± 1.1 SD (n = 40) per nest and the average fledging success was 1.8 ± 1.1 SD (n = 42) young per nest. While we observed a nest success rate of 86% (n = 50), there are no indications of population growth. The global population size is on a declining trend and the distribution range is shrinking. Very little information is available on predators, post-fledging survival, dispersal and mortality. Within Bhutan, despite good breeding success, the population has remained low and potentially declining. However, we have no data on yearling/juvenile survival rate. In the recent years, their distribution has shifted from altitudes between 600-1,500 m to wider regions between 100-1,800 m, undoubtedly as a consequence of the activities of humans (rafting, hydro projects and general disturbance). There is also a noticeable decrease in population in some of the older habitats and most of the oldest nesting sites have been abandoned. The small and fragmented population with a restricted range and small gene pool is further threatened by habitat loss due to infrastructure development, hydropower dams, extractive industries, and climate change in the region. Our long-term monitoring and conservation has filled many information gaps and provides important implications including the need for securing ex-situ gene pool, conservation breeding, more coordinated and impactful in-situ conservation efforts to save this species from extinction.

Monitoring the Critically Endangered White-bellied Heron, Ardea insignis, in Namdapha Tiger Reserve, Arunachal Pradesh, India

The White-bellied Heron (WBH, Ardea insignis) is one of the most threatened birds in the world. India may host the largest population of WBH, but there have been limited population surveys. Namdapha Tiger Reserve (NTR), in the north-east of the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh, has been noted as a strong-hold for the species where sightings have been recorded and estimates thus far are of 5-6 individuals remaining. However, regular monitoring of the species has been a challenge due to lack of resources and with more attention being given to monitoring large and charismatic mammals found in the Tiger Reserve. The purpose of this study was to assess the presence of the WBH in this region.

This study was carried out during 2021-2022. We laid out 32 transects each 1-2 km in length and 30-50 m in width in the known and potential habitats of WBH along the Deban, Noa-dehing and Namdapha rivers in NTR. These transects were walked (by 2-3 observers) searching for the WBH in the period between October 2021-March 2022. Each transect was monitored four times. Environmental parameters, activities of the birds and habitat characteristics were recorded. These preliminary surveys resulted in 18 direct sightings of the WBH including at least ten different birds. Eight of these sightings were repeats specifically in transects which were located in sites that were previously reported to have WBH in NTR. Six of the direct sightings were in sites from where WBH has never been sighted or reported in published literature before.

Anthropogenic activities like fishing, using river banks as thoroughfare, road construction, agriculture activities and sheer presence of a large number of people in pristine WBH habitats have the potential to be a direct threat to the species or its habitat. We hope some of these are short term and will reduce drastically when the Miao-Vijanaygar road (which cuts across the core area of the Reserve) construction is completed. While areas in core areas of NTR may provide a better habitat for the species in terms of lesser threats and disturbances, it is imperative to monitor the species in its known habitats as establishing its presence in unknown areas will be challenging considering the terrain and the shy and elusive nature of the bird.

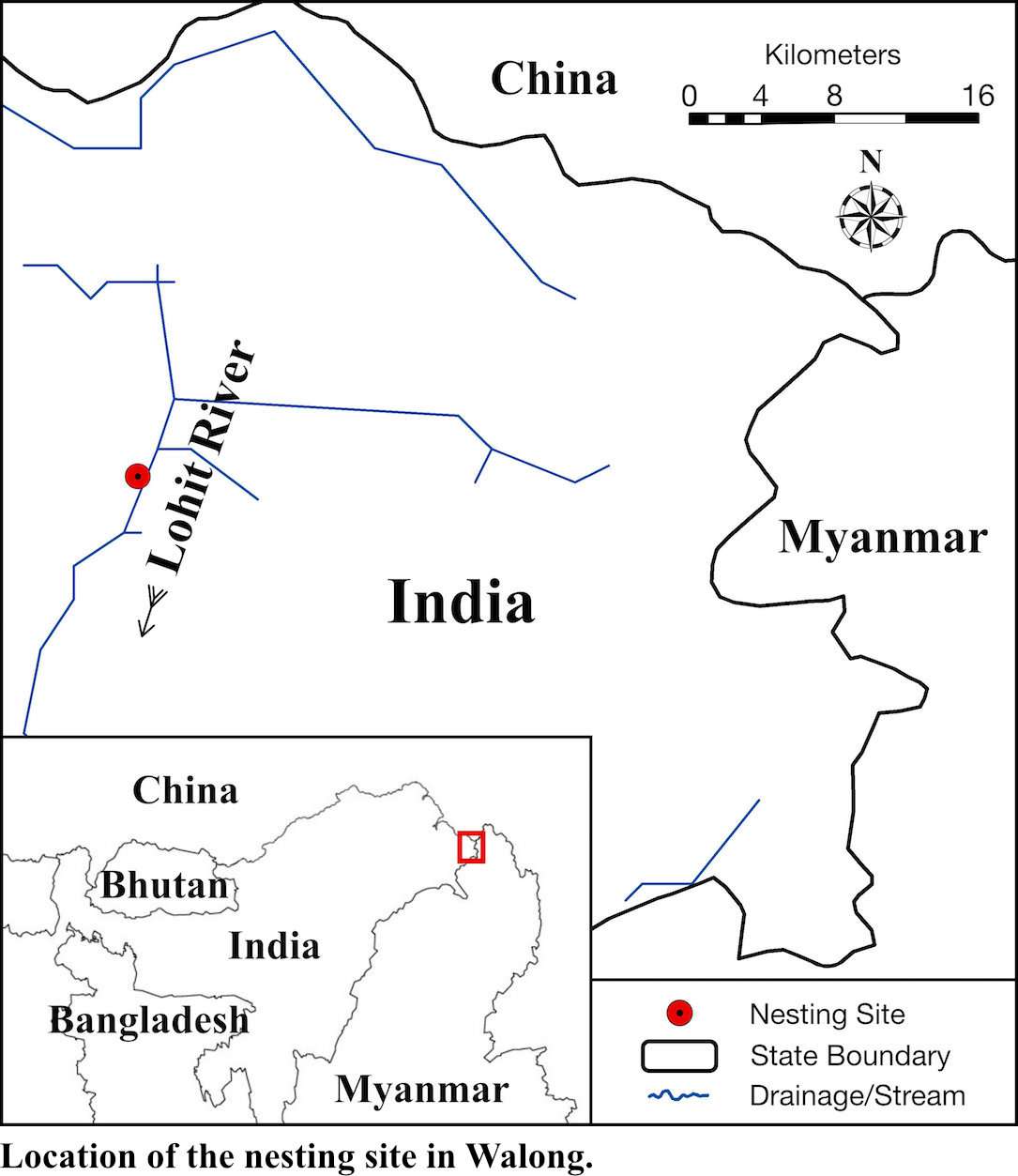

Implications and observations of a newly discovered White-bellied Heron Ardea insignis nesting site in India

The White-bellied Heron Ardea insignis is a Critically Endangered bird with an estimated global population of around 200-250 individuals. According to the IUCN SSC White-bellied Heron Working China Group, the confirmed population throughout its range is less than 60 individuals. The White-bellied Heron is presently distributed in Bhutan, Northeast India and Myanmar. On 16 April 2021, a pair of White-bellied Heron was recorded along with a nest in Walong, adjacent to the Indo-border in Arunachal Pradesh. The nest was recorded in a Merkusi’s Pine (Pinus merkusii) forest close to Walong Township at 1,250 m asl on river Lohit, about 11 m from the ground. This is the second nesting record in India. Previously Namdapha Tiger Reserve was the only nesting site in India with a population of at least 7-8 individuals. The record in Walong is vital due to the proximity of Walong to other White-bellied Heron habitats like the Namdapha and Kamlang Tiger Reserves. It is also close to the priority sites which the Working Group identified. The sightings in Walong give us the scope to explore other areas close to Walong, including China. Preliminary surveys were carried out in Walong and the nearby areas to understand their habitat, behaviour, the associated threats, etc. Our observations show that the birds are highly adapted and tolerant toward humans. It is also significant since the birds were nesting and occupying the areas very close to human settlements, which contradicts our established perception that the White-bellied Heron in India is shy and avoids human presence. Also, household questionnaire surveys were carried out in 14 villages, including the Walong Township and the villages covering the areas from Kaho (the nearest village to the Indo-China border) to villages downstream from Walong Township. In the Kobo Collect mobile app, a semi-structured questionnaire was created. The questionnaire surveys were mainly directed toward men since they are primarily engaged in hunting. Sixty-four people responded to the questionnaires. Our findings show that 59% of the respondents had never seen a White-bellied Heron, 12% had seen it recently, and 29% had seen it in recent years. This pattern indicates that the species could have mainly remained unnoticed due to their small number and camouflaged nature. We could not find any hunting records of the birds, but the Meyor and the Miju Mishimis, the dominant tribes of the area, practice traditional hunting. We also found traces of forest fire in the nesting site.

A Coordinated response to the plight of the White-bellied Heron (Ardea insignis)

The Critically Endangered White-bellied Heron (Ardea insignis) is the one of the world's rarest birds and is the second largest heron. As such, a group of international and range-state based conservationists, government representatives and scientists, came together in Guwahati, India, in December 2014 for a Conservation Strategy Workshop. As a result, the White-bellied Heron Working Group was formed under the IUCN SSC Heron Specialist Group; International and Regional Coordinators were appointed and a global Conservation Strategy (Price and Goodman 2015), was produced in November 2015. This was followed by a second International Workshop held in Bhutan in late November 2015. Survey work in China got underway in 2015 to try and understand the likelihood that a population still survived in China or not, sadly no birds were located. However, in December 2019, a young bird was found injured and rapid action on the ground saw the bird enter captivity to later be released. The collective and expeditated effort for this single individual was impressive – involving scientists and zoo professionals from China, Japan, Singapore and Europe. Sadly, the bird did not survive, and its satellite transmitter was later found having been deliberately removed by people.

In India, the White-bellied Heron Coordinator held national meetings and field work increased subsequent to the two international workshops. The Working Group was able to locate some funding for parts of this field work and in 2018 help to organise a workshop and publish a subsequent report on priority sites for survey within India (White-bellied Heron Working Group 2019). That publication has since been guiding field work being undertaken by various individuals and organisations and in-fact identifying new records of birds in India.

Soon after the second international workshop, one of the top priority actions was implemented when two birds were fitted with satellite transmitters in Bhutan in June 2016. Unfortunately, the data were poor but the training delivered by a European transmitter expert to the team in Bhutan was invaluable. In 2020, the captive breeding centre for White-bellied Heron was finally completed by the Royal Society for Protection of Nature (RSPN) and the Bhutanese government and despite the presence of COVID, three fledglings were brought into captivity in 2021. The Bhutanese team had undergone two previous training efforts (at European zoos to work with large waterbirds which might have similar needs and risks) to help prepare for the role of caring for one of the world’s most threatened birds. This was organised via the Working Group (starting in 2017) and appears to have helped the capable team at RSPN. In recent months, an injured bird has been found and also brought into the breeding centre. The plans continue to harvest chicks and/or eggs from the wild in subsequent years and to increase the capacity of the centre as soon as possible.

The IUCN SSC White-bellied Heron Working Group has been working through its members to provide multi-pronged support at levels ranging from funding to capacity building. There is now a small yet committed community of implementors and advisors placed across range states and the globe. While the role to coordinate this group could be more fully realised, having any such working group in the context of such an underfunded and overlooked species has proven that traction can be had with more concerted and coordinated efforts. In the future, it is hoped that India and Bhutan will remain the strongholds of the species and that protection can continue and be scaled up, while captive breeding efforts can come to fruition to provide a security stock for the species.

Literature Cited

Price, M. R. S. and G. L. Goodman. 2015. White-bellied Heron (Ardea insignis): Conservation strategy. IUCN Species Survival Commission White-bellied Heron Working Group, part of the IUNC SSC Heron Specialist Group. [online]

White-bellied Heron Working Group. 2019. Prioritising search areas for White-bellied Heron in India. IUCN Species Survival Commission White-bellied Heron Working Group, part of the IUNC SSC Heron Specialist Group. [online]

Targeted water management is key to recovery of the endangered Australasian Bittern, Botaurus poiciloptilus

The Australasian Bittern (Botaurus poiciloptilus) is a cryptic, globally endangered waterbird and the most threatened bittern in the world. Over the past decade, concerted efforts, including substantial public funding, have promoted the species as a flagship for wetland conservation and provided new insights into the conservation status, key threats and required conservation actions. The global population appears to be around 2,000 individuals and still in decline, particularly in New Zealand. The new Action Plan for Australian Birds estimates the national population at 1,300 birds (Herring et al. 2021a), concentrated in the Riverina region of New South Wales, where rice fields support 500-1,000 birds, with the most important natural wetlands comprising the Barmah-Millewa, Lowbidgee and Fivebough-Tuckerbil systems. Northern Victoria, especially around the Kerang region, contains several key wetlands, e.g., Hird and Johnson Swamp, while southwestern Victoria, including adjacent parts of southeastern South Australia, can also support relatively large numbers, notably at Bool and Hacks Lagoon, and Pick Swamp. With the exception of rice fields, almost all of these bitterns occur in protected areas and game reserves. Tasmania and southwestern Australia each support a small, relatively isolated subpopulation of less than 100 individuals. In Australia, the increasing severity and frequency of drought is now considered the key threat, emphasizing the impacts of climate change and the importance of drought refuges. Dry periods reduce the environmental water available for key bittern sites in the Murray-Darling Basin and amplify water-use efficiency measures in rice fields that are undermining successful breeding opportunities (Herring et al. 2021b). Improved water management across all wetland types could maximize the benefits to bitterns. For example, providing a sufficient hydroperiod for successful breeding that also incorporates a drying phase can maintain the preferred early successional stages of vegetation and maximize prey abundance. Incentives for bittern-friendly rice farming and targeted environmental water management at key wetlands should be prioritized, while the potential impact of fox and cat predation needs to be assessed. Despite increased attention, the conservation status of the Australasian Bittern remains grave and greater management effort is urgently required.

Literature Cited

Herring, M. W., P. Barratt, A. H. Burbidge, M. Carey, A. Clarke, S. Comer, B. Green, R. Pickering, C. Purnell, A. Silcocks, V. Stokes, E. Znidersic, R. P. Jaensch and S. T. Garnett. 2021a. Australasian Bittern Botaurus poiciloptilus. Pages 222-224 in The Action Plan for Australian Birds 2020 (S. T. Garnett and G. B. Baker, eds.). CSIRO Publishing, Melbourne, Australia.

Herring, M. W., W. Robinson, K. K. Zander and S. T. Garnett. 2021b. Increasing water-use efficiency in rice fields threatens an endangered waterbird. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 322: 107638. [online]

Current status of the Humblot's Heron (Ardea humbloti) in Madagascar

The Endangered Humblot's Heron (also known as Madagascar Heron, Ardea humbloti) breeds in Madagascar with a recent record in Mayotte. To strengthen its conservation, investigations were carried out through literature reviews and field expeditions undertaken from 1993 to 2019 in Madagascar for population assessment and trend evaluation. Waterbird censuses have been conducted twice a year when possible. Trend analyses were conducted using Trends and Indices for Monitoring data (TRIM) software based on 26 years of survey and population estimates from 2010 to 2019. Missed values for unvisited sites were evaluated to complete the count by using indices from monitoring data. Based on 683 records, the species occurred in various types of wetlands from marine and coastal habitats to inland wetlands with reconstructed habitats throughout Madagascar. The Humblot's Heron displayed a skewed distribution with higher concentration along the western coastal area, it becomes rare in the southern part and absent along the eastern part of the country. The 2019 population was evaluated at 1,290 mature birds with a minimum of 645 breeding pairs. Most (59.1 %) of the recorded population of the species occurred inside Protected Areas in Madagascar, where several instances of large numbers were noted, e.g., Manambolomaty lakes complex (137 individuals, 2003), Mahavavy Kinkony wetland complex (49 individuals, 2017), Baly Bay (43 individuals, 2000) and Mangoky Ihotry wetland complex (37 individuals, 2019). The species was recorded nesting in colonies but some of the time (31.4 %) it was seen alone, with one record in Mayotte. This heron breeds all year with 76.6% of breeding records seen between September to January. Most of its breeding area was recorded in western Madagascar. The population showed a moderate but significant decline of 1.4% per year (P < 0.01). The main threats are 1) habitat destruction such as slash and burn activities to convert wetlands to agricultural lands, 2) impacting reproductive success through the collection of eggs and fledglings, especially at their breeding colony sites, 3) human disturbance at nesting and foraging sites by over-fishing activities and the collection of aquatic plants, 4) the invasion of alien species, mainly the Water Hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes), which limits the heron’s foraging area and 5) the possible hybridization with its congener the Grey Heron (Ardea cinerea), of which at least one possible case was seen (see photo). A Humblot's Heron Action Plan is needed to preserve this species including: 1) reinforcing conservation action inside Protected Areas, 2) strengthening mass media communication and education about the species, 3) establishing a Community Conservation Group outside of the Protected Area and 4) completing a bioecological study of the species in Madagascar.

Literature Consulted

Jeanne, F., A. Laubin, B. Ousseni, C. Crémades, C. Pusinéri and P. Lizot. 2015. Bilan 2010-2015 des Ardéidés nicheurs et menacés de Mayotte. Gepomay, Mayotte, France.

Langrand, O. 1995. Guide des oiseaux de Madagascar, Delachaux and Niestlé, Lausanne, Switzerland.

Rabarisoa, R. 2001. Variation de la population des oiseaux d’eau dans le complexe des lacs de Manambolomaty, un site Ramsar de Madagascar. Ostrich 72 (Supplement 15): 83-87.

Rabarisoa, R., O. Rakotonomenjanahary and J. Ramanampamonjy. 2006. Waterbirds of Baie de Baly, Madagascar. Pages 374-375 in Waterbirds around the World (G. C. Boere, C. A. Galbraith and D. A. Stroud, eds.). The Stationery Office, Edinburgh, U.K.

Sartain, A. and A. F. A. Hawkins (eds.). 2013. The birds of Africa. Volume VIII: The Malagasy region. Christopher Helm, London, U.K.

Observations of the world’s largest known breeding colony of Agami Herons (Agamia Agami) at Tapiche Reserve in the Northeastern Peruvian Amazon

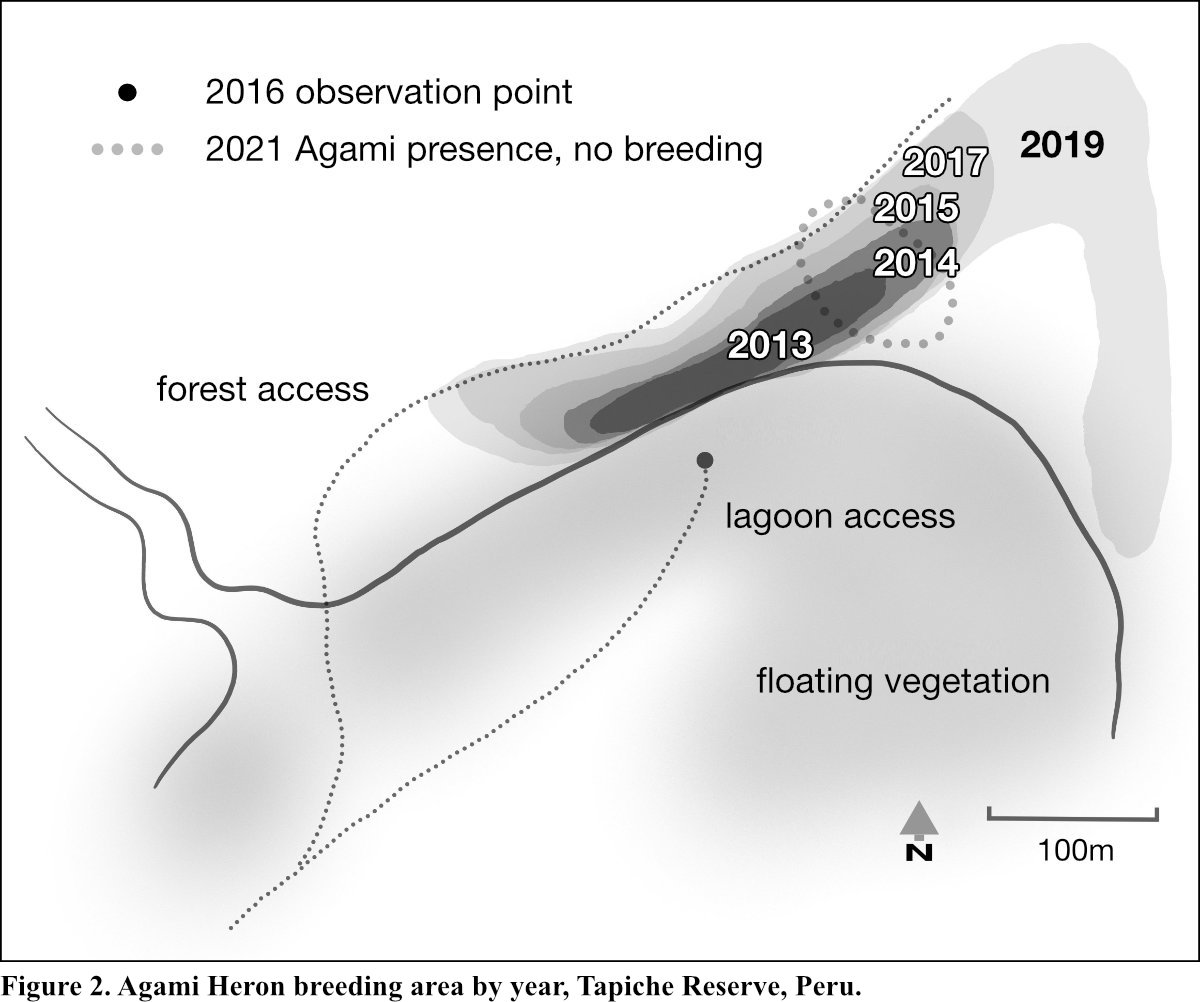

The Agami Heron (Agamia agami) is widespread in the Neotropics but remains a poorly understood species; little has been confirmed regarding population sizes and trends, seasonal migration patterns and the Agami’s role in the wetland communities it inhabits. In this study, we explore these topics through observations made from 2013 to 2021 of a large mixed-species heron breeding colony, including Agami Herons, located at the Tapiche Reserve in northeastern Peru. Situated in a seasonally flooded forest at the edge of a lagoon, the two-hectare breeding colony is observable via boat. An exhaustive census of the entire breeding area was not possible due to the large size of the colony and inadequate personnel and resources to complete the task. For the March 2017 inventory, we applied the area count technique in transects of approximately 100 m2 spaced at five intervals along the length of the colony. The count was taken when the first Agami hatchlings were about 5-7 days old, and the Agami Heron was the only colonial heron species nesting in this area. Using the formula in the Agami Heron Working Group protocol for extrapolation, (the number of nests in the counted surface × real colony surface/counted surface), the estimated number of Agami nests in 2017 was 15,450. An example of nest density at the nesting site can be seen in Figure 1. The Agami were typically present at this site between January and July, outside of which the colony site was deserted. Occupation of the area is shown by year in shades of grey in Figure 2. Observation was limited to a single access point in 2016 due to an overgrowth of floating vegetation. The Agami were completely absent in 2018, when the nesting area did not flood, and in 2020, when the flood was low and delayed. The Agami Herons were the first herons to occupy the breeding ground during years of breeding success, with Boat-billed Herons (Cochlearius cochlearius) arriving 4-8 weeks later in equal thousands of numbers as the Agami. The Boat-billed Herons typically arrived around the time the earliest Agami hatchlings were old enough to cling to branches outside the nest. The Boat-billed Herons appeared to use existing Agami nests rather than building new structures, and Agami fledglings were often observed perched just next to nests occupied by Boat-billed Herons incubating eggs. In the years that the Agami did not nest, the Boat-billed Herons arrived in far fewer numbers and also failed to breed. Territorial disputes between the Agami and Boat-billed Herons were common. Eight additional waterbird species were resident in the rookery area, some breeding concurrently with the Agami. These included Cocoi Heron (Ardea cocoi) - very common, Neotropic Cormorant (Nannopterum brasilianus) - very common, Anhinga (Anhinga anhinga) - very common, Hoatzin (Opisthocomus hoazin) - very common, Great Egret (Ardea alba) - very common, Black-crowned Night Heron (Nycticorax nycticorax) - common, Snowy Egret (Egretta thula) - common and Wattled Jacana (Jacana jacana) - very common. Nearby, in other parts of the lagoon, were also Striated Heron (Butorides striata) - very common, Horned Screamer (Anhima cornuta) - very common and Azure Gallinule (Porphyrio Flavirostris) - uncommon. Primates, raptors and reptiles were seen preying upon Agami eggs and young. Prior to the establishment of the reserve in 2010, local people exploited the rookery by collecting eggs and hunting adult birds almost to the extinction of the colony. The Agami responded rapidly and positively to protection of the rookery and showed resilience to isolated episodes of drought. Some observations suggest, however, that these birds are challenged by consecutive years of adverse climate conditions. An understanding of the Agami’s foraging behavior and range while breeding, movement patterns outside the breeding season and alternate breeding locations, if any, during atypical flood years would be of immense value to conservation efforts for this iconic heron species.

Overview on the diversity, biogeography and conservation of Herons in Ecuador

Twenty-three species of herons have been reported in Ecuador, including Agami Heron (Agamia agami) classified under the IUCN threatened category of Vulnerable and Zigzag Heron (Zebrilus undulatus) considered as Near Threatened. Few studies have focused explicitly on the herons of the country, and little information is available about their current distribution, natural history and ecology, population trends and conservation status. We produced an integrated and updated assessment of the species richness and biogeographic patterns for all species and subspecies of herons of Ecuador. This study is based on a large species occurrence dataset obtained from different sources, including fieldwork, scientific literature, grey literature, natural history museums, open data biodiversity databases and private expert databases. Analyses emphasise wetlands and other localities that are part of the National System of Protected Areas of Ecuador or are classified as Important Bird Areas or RAMSAR sites. We identified causes driving population changes (declines or increases), including habitat changes, illegal hunt, invasive species or human-heron conflicts. Finally, we applied the IUCN Red List categories and criteria to evaluate the extinction risk for all species at the national level and provide suggestions for implementing research and conservation actions.