Green Heron

Butorides virescens (Linnaeus)

Ardea virescens Linnaeus, 1758, Syst. Nat. 10th Ed., p. 144: Based on Ardea stellata minima Catesby, Nat. Hist. Carolina, 4:80, Pl. 0. America = coast of South Carolina.

Subspecies: Butorides virescens anthonyi (Mearns) 1895: Seven Wells, Salton River, N Baja California; Butorides virescens frazeri (Brewster) 1888: La Paz, Baja California; Butorides virescens bahamensis (Brewster) 1888: Watling’s Island = San Salvador, Bahamas.

Other names: Green-backed Heron, Little Green Heron, Little Crabier, Poor Joe, Gaulin, Water Witch, Pond Bird in English; Garcita Verde, Garcita azulada, Garza Rayada, Chicuaco, Caga Leche, Cuaco, Crá-Crá, Martinete in Spanish; Heron vert, Krabye rivié, Kio in French; Groene reiger in Dutch.

Description

The Green Backed Heron is a small, stocky dark-backed heron with a thick neck, relatively heavy dark bill, thick short legs, and maroon neck.

Adult: The adult has a glossy green black cap with erectile plumes forming a shaggy green black crest. The bill is brown black with the lower bill tending to dusky green and yellow at the base. A cream buff stripe runs from the bill to under the eye. The irises are orange or yellow. Lores are dull yellow green, with lower portion black. The side of the head, neck, breast and upper back are chestnut, maroon. The throat and the upper breast are streaked and spotted in white, forming a vertical stripe, yellow brown in the center and edged in grey. Back is dark grey to black with green to blue cast. The upper back feathers are elongated to form modest plumes. Upper wings are grey to black with buff edges to feathers. Flight feathers are black with buff edge. Under parts are brown grey to grey in most forms. The legs are yellow orange.

In breeding, the head and crest are glossy black, with elongated erectile plumes. The side of the head, neck, breast and upper back are chestnut. The irises turn deep orange in courtship setting off blue black lores. The bill becomes glossy black and the legs glossy orange.

Variation: Females are smaller (Davis and Kushlan 1994), and also duller and lighter colored, especially during breeding. There are four recognized geographical forms (Payne 1974). Virescens is as described above. Anthonyi is distinctly larger and has more birds with paler brown necks. Frazeri has a dark necked that appears more purple than brown. Bahamensis averages smaller and paler than North American birds.

There also is variation from north South America, through Central America and the West Indies. Birds from this region show a range of neck coloration from grey through brown to maroon (Payne 1974). Birds from Guatemala through El Salvador and Costa Rica average smaller than North American birds but there is considerable overlap and no consistent coloration differences. Birds from the West Indies, the subspecies maculatus of Voous (1986), average smaller than east North American birds but there is considerable overlap with both North American and Mexican birds so no taxonomic distinction is recognizable (Steadman et al. 1997). Birds in Costa Rica show variation and distinctiveness in morphology among populations, although with considerable overlap (G. Alvarado in prep.). A red brown phase occurs in Cuba (Raffaele et al. 1998). A partially white heron was reported from California (Garrett 1994).

In addition to variation within Butorides virescens、 intergradation occurs with South American Butorides striata in southern Central America, north South America and the south West Indies which is accountable for the range in neck colors in the region (Hayes in prep.) Birds from Panama with brown grey necks were once described as the subspecies patens and now are also considered intermediate between western Panamanian virescens and South American striata.

Juvenile: The juvenile plumage differs substantially from the adult. The juvenile bird has a green grey crown with a slight crest. Bill is brown black above and yellow below. Irises are yellow. The lores are yellow green. The line under the bill is buff white bordered with black. Throat and neck are buff white with dark chestnut streaking. Its side of head and neck yellow brown broadly streaked in chestnut to grey. Back and wings are dark green grey. The wings are dark green grey, with have buff white spots. Flight feathers are dark grey with green cast, tipped in white. The under parts are brown to buff white with buff spots. Legs are yellow green.

Chick: The hatchlings are gray brown above, with a downy crest, and light grey below. Skin on head is green, lores yellow green. Eye ring is green yellow. Bill is yellow tipped dark. Throat is white. Legs are green, turning yellow green.

Voice: The characteristic call of the Green Heron is the “Skeow” Call. Variously rendered as “skeow”, “skow”, “skyow”, it is an alarm, flight and advertising call. The “Skuk” call is the disturbance call, rendered as “ku, ku, ku” or “skuk, skuk, skuk”, “kak, kak, kak”, or “ kek, kek, kek”. The “Showch” Call, rendered “show, ch” or “ ow ch” is an advertising call. The “Rah” call, rendered “raaah” or “raah, raah” is the agonistic call, used in Forwards and other times. The “Arroo” Call, “arroo, arroo”, is used with the Stretch display. Adults also use Bill Snaps in courtship. “Cuck” call, “cuck, cuck”, is used when approaching young. Young beg with “tik, tik, tik, tik”.

Weights and measurements: Length 41-46 cm. Weight: 200-250 g.

Field characters

The Green Heron is identified by its thick maroon neck, its black cap, large bill, green tinged grey black back. It flies with deep, slow, steady wing beats, 2.8-3.8 per second with its head retracted and legs extended beyond the body. In flight at a distance it appears black. It is often seen flying after being disturbed. Then it flies with head out and feet dangling and gives the characteristic Skeow Call. It also usually relieves itself, leading to some vulgar common names. It lands after a short glide with head and neck extended. This disturbance flight behavior is one of the best identifiers.

Its chestnut not grey to rust neck distinguishes it from the Striated Heron. It is distinguished from all other herons by its combination of dark crown, relatively large bill, uniform maroon neck and side of head, yellow lores and legs, posture, behavior and Skeow Call.

The immature is distinguished by its brown color and dark cap, as well as by posture and behavior. It is distinguished from immature night herons by being smaller darker, with darker cap, longer neck and slighter bill. It is distinguished from the juvenile small bitterns by its larger size, dark crown, and darker upper parts. It is distinguished from the American Bittern by smaller size and lack of a black neck mark. It likely is not distinguishable from the Striated Heron.

Systematics

The systematic position of the Butorides has been a matter of uncertainty for some time. These birds are sometimes placed with other small herons in Ardeola (Payne 1979), and molecular, behavioral, and morphological evidence confirms their close affinity with these birds (Payne 1974, Payne and Risley 1976, Sheldon 1987, K. McCracken pers. comm.). Butorides herons are however distinctive both molecularly and morphologically, and so are best retained in their own genera. Butorides and Ardeola together are most closely related to the Ardea.

Specific and infraspecific systematics have also been a matter of considerable study and discussion, particularly focusing on the relationship between North American birds with their maroon necks and South American birds with their grey necks. In recent decades advocates have suggested combining the forms into a single species on the basis of morphology and intermediacy of the plumage of particular specimens (Payne 1974, AOU 1993). Other advocates have suggested separating them into two species on the basis of lack of intermediacy of particular specimens (Wetmore 1965, Voous 1986, Monroe and Browning 1992, AOU 1998). Birds intermediate between virescens and striata are documented from the nonwintering season from the Lesser Antilles, Tobago, Panama, Cocos Islands, Colombia, Venezuela, the Dutch West Indies, and Surinam (Payne 1979, F. Hayes in prep.) But alternative interpretations have been made (Voous 1986). Certain specimens have been subject to alternative interpretations as to whether they have or do not have juvenile characteristics or may or may not be migrants. The fact that including or excluding certain specimens is so critical to the findings suggests caution is needed in drawing conclusions based on available specimens. However, the latest re-interpretation of available specimens shows a range of intermediate birds indicating an extensive zone of hybridization in the south Caribbean islands and also in southern Central America (Hayes in prep).

The North and South American Butorides undoubtedly represent forms that have been isolated from each other for some time. Molecular evidence is tending to support differentiation of the two species (K. McCracken pers. comm.). So this book follows AOU (1998) in recognizing Butorides virescens as separate from Butorides striata, deviating from the approach in Hancock and Kushlan (1984). However, variability and intermediacy in the zone of contact suggests that the two forms interbreed freely. By traditional concepts, the two Butorides would be considered conspecific (Hayes in prep.). The final word is not yet in on the species limits of Butorides.

Range and status

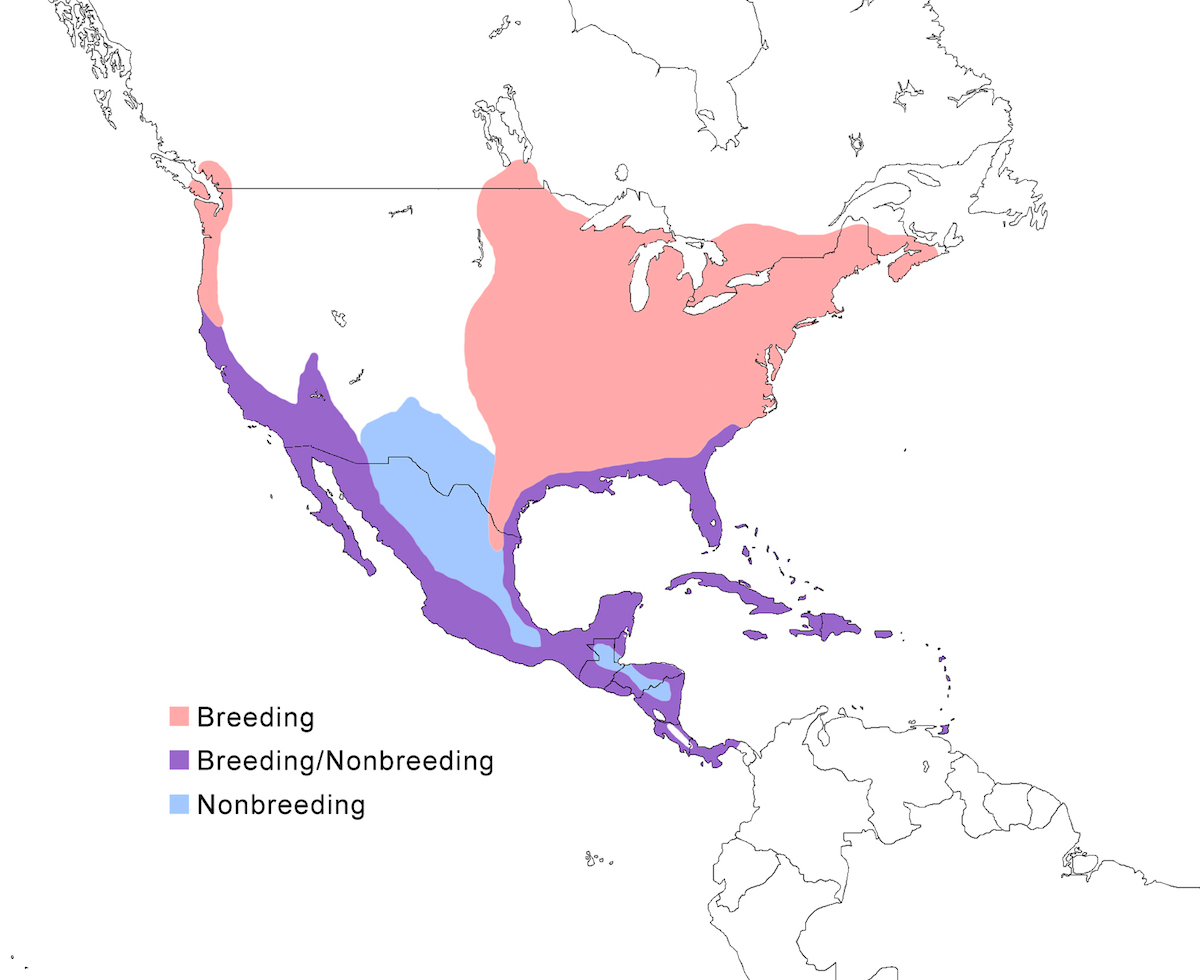

RANGE: The Green Heron occurs in North America, Central America, and the West Indies. The status of the species at the southern edge of its range requires additional study.

Breeding range: Virescens breeds in east, central and south North America from south Canada (New Brunswick, south Ontario, south Quebec, Manitoba) (Koes and Taylor 1991, Grieef 1991), and north Central United States (east North Dakota, east South Dakota, east Colorado), through central and south United States (Florida, Texas, New Mexico), mainland Mexico, Central America to central and east Panama and Caribbean islands off the coast of Central America and Venezuela (Aruba, Curacao, Bonaire, Los Roques, Margarita Island, Tobago), and the Greater and Lesser Antilles. The situation in Tobago is particularly interesting, in that evidence suggests that there has been a shift in the population from one that was intergrading between striata and virescens to one dominated by virescens (Hayes in prep.).

Anthonyi breeds in west Canada and north west United States, in south west British Columbia (to south east Vancouver Island) north west United States (west coastal Washington, Oregon (Jobanek 1988), California, Nevada, south Utah, Arizona), and Mexico (north Baja California, Sonora). Frazeri breeds in west Mexico (Baja California Sur). Bahamesis breeds in the Bahamas Islands.

Nonbreeding range: Virescens occurs in nonbreeding season in the southern part of its breeding range, in the south United States (south Carolina, Florida to Texas), Caribbean (Bahamas Islands, Cuba, Cayman Islands, Jamaica), Mexico including the interior, Central America, north South America from south Colombia (Scott and Carbonell 1986), coastal Venezuela and offshore islands (Bonaire).

Anthonyi occurs in nonbreeding season in the south part of its breeding range, south to west Mexico (Guerrero, Chiapas) more rarely to Central America (El Salvador, Costa Rica). Frazeri and bahamensis are sedentary, as far as is known, wintering on their breeding range.

MIGRATION: Northern populations have a dispersal or wandering period at the end of nesting, August–September, which then merges with migration in October. Migration is typically, although not always, in flocks at night. They call in flight to maintain contact (Brady 1990-1991). Northern populations tend to be partially migratory, with northernmost birds moving south but some staying rather far north. Western virescens migrates south to Mexico and Central America. Birds from the central Continent move to Texas, and Florida to Mexico, Central America and the Greater Antilles. Eastern birds move south to and through Florida, Greater Antilles, and Cayman Islands. Return migration is March–April over most of the range, but May in north west United States. Anthonyi move south to west Mexico and Central America.

Dispersal records for virescens include Cocos Islands, Guyana, Surinam, Greenland, England (Ross and Bell 1985), Scotland (Gordon 1988), France (Rault 1995), Hawaii (Paton and MacIvor 1983), and the Galapagos (Vargas 1996).

Status: The Green Heron is widespread and numerous. Populations appear to be increasing in most areas in North America, although local populations reductions appear locally due to habitat modification (Davis and Kushlan 1994). Populations appear to be largest in Florida and Louisiana (Butler et al. 2000). The range has been expanding in the middle of the continent along impoundments and managed river systems and northward along the Pacific Coast. It is abundant in Central America (Butler et al. 2000). It is common in West Indies (Raffaele et al. 1988).

Habitat

The Green Heron is a bird of swamps and marshes, lined with brush or trees. It occurs in both inland and coastal habitats especially along small and large brushy marshes, river swamps, mangrove swamps, the edges of forested rivers and streams, lake margins, salt flats, woods, sand, muddy or rocky shores, pools, and in human made habitat such as reservoirs, impoundments, ditches, canals, ponds, and orchards.

Foraging

Green Herons are stand and wait predators. They feed solitarily, defending feeding sites and sometimes a larger territory. Birds are aggressive in defending their space, and birds that are sedentary may occupy feeding territories long term and may nest within it (Kushlan 1983). Herons defend their sites with Forward displays (see Courtship). They also use Supplanting Flight, Supplanting Run, and Pursuit Flights.

They feed in loose groups and aggregations if prey is especially available. Feeding occurs at nearly any time, day or night, including at night by artificial light and along the coast according to the tides. It feeds in very shallow water (< 5 cm), and is more successful in shallow than in deep water, presumably because of the avoidance behavior of the fish (Kramer et al. 1983).

Its feeding behavior is primarily Standing, in shallow water or on shore or on a perch overhanging water such as branch, rope, boat, or rock. It uses a very characteristic Crouched posture, legs bent and body parallel to the ground. It Crouches so low that sometimes the lower leg nearly touches the substrate. The head may be withdrawn ready for a Bill Stab or extended out towards the prey ready for a Bill Lunge. It is a patient feeder, standing for many minutes examining the water intently waiting to see a prey item. On its usual feeding grounds, it has favored perches to which it returns.

One common variant of Standing behavior is perching on a branch or some other structure above the water. The heron waits patiently, drawing closer to the water if a prey emerges. It then uses its characteristic Forward Throwing behavior, in which grasping the branch, it throws its body toward a prey item but keeps its hold on the branch. Sometimes, it Hangs Upside Down to catch fish beneath its perch (Nesbitt 1984). When the prey is too far away, the heron will Dive or Jump from its perch into the water below.

It intersperses Standing with hopping from one feeding station to another or by slow Walking. It Walks along the edges of the water, or along branches in a slow and methodical manner, continuing in its Crouched posture. It Walks readily among branches, both from perch to perch and also to transition to an open place from which to fly. While Walking, a heron may use Head Swaying or Neck Swaying to locate prey.

It also does things to stir up its prey, such as Walking Quickly, Foot Stirring and Foot Raking. When feeding actively, it often flips its tail and raises and lowers its crest. It uses Standing Flycatching to catch insects, aerial techniques of Feet First Diving and Plunging (Knight 1994) and Standing Flycatching.

Its most intriguing behavior is Baiting, which has been reported from a number of places. These birds have been recorded as using bread, maize, popcorn, fish pellets, feathers, twigs, leaves, berries, flies and plastic (Davis and Kushlan 1994). These observations are clearly examples of tool use (Lovell 1959, Preston et al. 1986, Higuchi 1988a, Kurosawa and Higuchi 1993, Harvey 1999, 2000). Birds have been observed to dig up earthworms and then use them for bait and to break sticks to use for baiting (Davis and Kushlan 1994).

Green Herons both by day and also at night, especially under artificial light (Hayes and Hardy 2001). They roost when not foraging and spend much of the time there preening (Davis and Kushlan 1994). In the evening they roost alone or in small groups. In larger mixed species groups they tend to segregate themselves. It often gives the Skeow Call when flying to and from roosts. It responds to disturbance with a Bittern Stance.

The Green Heron is primarily a fish eater (e.g., Niethammer et al. 1983). Fish include a wide array of species, Fundulus, Lepomis, Notropis, Aphredoderous, Ictaluris, Esox, Cyprinus, Aplodinotus, Gobius, Dorosoma, Mendia, Anguilla. The variety suggests that they will eat anything they can catch and handle. But it is also extremely opportunistic with an overall highly varied diet including earthworms, leeches, adult and larval insects (larval dragonflies, damselflies, water bugs, diving beetles, grasshoppers, crickets, katydids), spiders (Dolomedes), crayfish, crabs, prawns (Palaemonetes), crayfish, snails, fish, frogs, toads, tadpoles, salamanders, lizards, snakes, rodents. Wiley (2001) observed a Green Heron taking nestlings from a weaver’s (Ploceus) nests, apparently the first record of this species eating a bird. They apparently consume vegetable matter, such as acorns (King 1985), but the frequency and value – if any – of this behavior remains to be determined.

Breeding

Nesting season varies geographically, both with season and with rainfall. Breeding in the United States is March to July with geographic variation, April–August in West Indies, July–September in San Blas Mexico in the rainy season, May–June in Jalisco Mexico (Hernandez and Fernandez 1999).

Green Herons nest at the edge or overhanging water in shrubs, bushes and small trees. For nesting, plants used include Rhizophora, Avicennia, Pinus, Cephalanthus, Salix, Acer, Quercus. They have been observed to use a bird nest box (Sandilands 1977).

Green Herons most typically nest solitarily in defended territories. However, they also nest in colonies (e.g., Maccarone and Gress 1993), usually in small single species groups of up to 100 nests, and also in mixed species colonies, where they tend to nest apart from other species. They nest not only with other herons, but cormorants (Phalacrocorax), darters (Anhinga), starlings (Sturnus), and Grackles (Quiscalus). The degree of sociality in nesting is likely a function of the local food supply (Kaiser and Reid 1987).

Nests are small structures, about 20 x 30 cm, made of twigs which sometimes are quite long, but usually thin. Nests are generally unlined but with a well developed cup, about 4.5 cm deep (Dickerman and Gavino 1969). They most typically are placed over water in bushes and trees, from ground level to about 2 m. However, higher nesting is not uncommon and they averaged over 10 m high in one colony (Kaiser and Reid 1987). Old nests of various species are often reused and reconstructed (Davis and Kushlan 1994). Or they may steal sticks from old nests and start anew. Females build the nest, but both birds make repairs while they incubate. Destroyed nests can be rebuilt quickly.

The Green Heron is an active and aggressive bird in its nesting behavior. The male chooses an advertising site, often an old nest. In northern populations, this occurs upon arrival from spring migration. It has a complex array of nesting behaviors (Meyerriecks 1960). Birds that are sedentary tend to have shorter and less intensive courtship, probably due to repairing of individuals holding adjacent territories (Kushlan 1983).

Courtship begins with birds making Circle Flights and Standing at the display site giving Skeow calls. At their most intense, the Circle Flights exhibit intense exaggerated flapping producing a “whoom, whoom, whoom” sound. In the flight, the neck is crooked, legs dangle, crest and back feathers are elevated, and Roo calls may be given on landing.

Males give Snap and Stretch displays. During the Snap, the bird moves its head down to its feet and bill snaps, with feathers slightly erect. It also shows bowing and bobbing components. The Stretch starts with the neck, head and bill straight up, and then bent back until the head almost touches the back. The back plumes are erected but other feathers are sleeked, the bird sways from side to side, the eyes bulge, the iris changes from yellow to deep orange, and the bird gives the Aaroo call.

The Green Heron is highly aggressive and defensive. Its Forward is given with the head and neck fully forward, feathers fully erect, especially the well developed crest, eyes bulging, bill open showing a red mouth (during breeding), tail flipping, all preceding a Bill Lunge (Davis and Kushlan 1994). As it lunges, it extends its wings and gives the Raah call. It also uses Supplanting Flight, over short distances and Pursuit Flights.

As pairing occurs, the displays change. The Stretch becomes more common after pairing. It is part of the Greeting Display, and is responded to by the female who gives a less intense Stretch. The Skeow call, Circle Flights, and Snap (as an advertising display) cease after pairing.

Eggs are pale green blue, but dull as incubation proceeds. They average 37 x 28 mm. The normal clutch is 3-5, range 1-7. Eggs are laid at two day intervals. They can have more than one clutch per year, particularly in the tropics (Dickerman and Gavino 1969, F. Hayes pers. comm.).

Incubation is by both sexes, beginning with the second egg, although there is evidence for beginning with the first egg. Incubation period is 19-23 d in Mexico, averaging 19-20 (Dickerman and Gavino 1969, Hernandez and Fernandez 1999). After the clutch is complete, the male incubates during the day, female at night. Parents also shade eggs in direct sun and heat.

Hatching is asynchronous over 3-4 days. Young are semialtricial, having limited movement. Chicks grow quickly, from 11.5 g at hatching to minimal adult weight at 2 weeks. They leave the nest and climb about on branches by one week, and can jump from branch to branch in two weeks. Chick growth is variable due to asynchronous hatching and differential growth, which is not heavily related to sibling competition (Gavino and Dickerman 1972). Chick call with “tik, tik, tik, tik”, and adults approach young giving a Cuck call. Young are fed initially into their mouth or on the nest, and then later by 1 week, young grasp parent’s bill. Young are left alone at 9-11 days and leave the nest at 16 days. They fly at 15-22 d. They leave the colony at 25 d.

Disappearance of eggs, usually attributed to predation, may be high in some areas. Egg and chick predators include snakes, grackles, crows (Corvis), raccoons (Procyon). In Missouri, USA, 78.8% of nests were successful.

Population dynamics

The usual age at first breeding is probably two. There are few reports of mortality by adults. There is little information on survival. Longevity is at least 7 years 11 months.

Conservation

Green Herons are common or even abundant over most of their range. High reproductive potential and broad habitat flexibility appear to compensate for many threats. The heron is subjected to shooting and trapping for food, pesticides, and habitat loss and alteration (Davis and Kushlan 1994). Disturbance to nests by human activity is a continuing problem in many areas. The primary conservation need, range wide, is the protection of habitat, especially wetlands (Kaiser and Fritzell 1984).

Research needs

Nesting success and population biology in various geographic areas need additional study. Further examination of migratory movements of populations and individual birds and the identification of important non-breeding sites in Mexico and the West Indies are needed. The systematics of the Butorides herons requires much addition as study, especially at the range overlap of virescens and striatus.

Overview

The Green Heron’s habitat is varied but typically is a thickly overgrown waters edge where it feeds from overhanging rocks, trees, or structures by Standing perched over, or by the water watching for fish to approach. This is a successful technique, but one requiring extraordinary skills at stillness, concentration and patience. This is a successful technique, but one requiring extraordinary skills at stillness, concentration, and patience. It also takes a territory free from disturbance (from other birds and sometimes from people) and sufficiently renewable food supplies. So, like other stand and wait herons, it must keep others from its feeding site and is highly effective in communicating its territory-holding status using its crest and vocalizations. Given the inherent constraints of a Standing-feeding mode of life, it also can make use of a remarkable array of more active and inventive feeding behaviors including using bait. It can feed at all times of day and night, sometimes responding to artificial light. This is a species that is very good at what it does best, but having a remarkable plasticity to deal with novel situations and opportunities.