Japanese Night-Heron

Gorsachius goisagi (Temminck)

Nycticorax goisagi Temminck, 1835. Pl. Col. Livr. 98, pl. 582: Japan.

Other names: Japanese Bittern in English; Martinete Japonés in Spanish; Bihoreau goisagi in French; Rotscheitelreher in German; Mizo-goi in Japanese; Bakaw-gabi in Pilipino (Philippines); Litou Yan in Chinese.

Description

The Japanese Night-Heron is a small, small billed chestnut and buff heron.

Adult: The Japanese Night-Heron has a chestnut cap with a short chestnut crest. The bill is relatively short and stout for a heron. The upper bill is dark brown; the lower bill is yellow. The irises are yellow and the lores are green yellow, forming a notable patch in front of the eye. The sides of the neck are buff brown. The upper parts are pale chestnut. The darker wings have blackish primaries with prominent broad tawny tips, giving the appearance of a black wing bar on an otherwise tawny wing. A pale patch on the forewing can be seen in good light. The under sides are brown with darker streaking and the flanks are slightly mottled. The legs are black green. In breeding, lores turn blue, and the bill turns green black.

Variation: The sexes are alike.

Juvenile: The immature is similar to the adult with a black brown crown and less chestnut head. Its neck is more spotted and streaked. Upper wings are paler.

Chick: The appearance of the chick has not been recorded.

Voice: A croaking “Buo” call, rendered “buo, buo” is the principal call in feeding and breeding. It is probably a contact and identification call.

Weights and measurements: Length: 49 cm.

Field characters

The Japanese Night-Heron is identified by its small size, tawny cap, short stout bill, and red brown upper parts. It is distinguished from the Malayan Night-Heron by its chestnut (not black) cap, shorter crest feathers, shorter and stouter bill, and tawny (not white) tips on primaries. It is distinguished from the Cinnamon Bittern by its bicolored back, chestnut wings and thicker bill.

Systematics

The Japanese Night-Heron is closely related to the Malayan Night-Heron. The relationships among these night herons are unclear.

Range and status

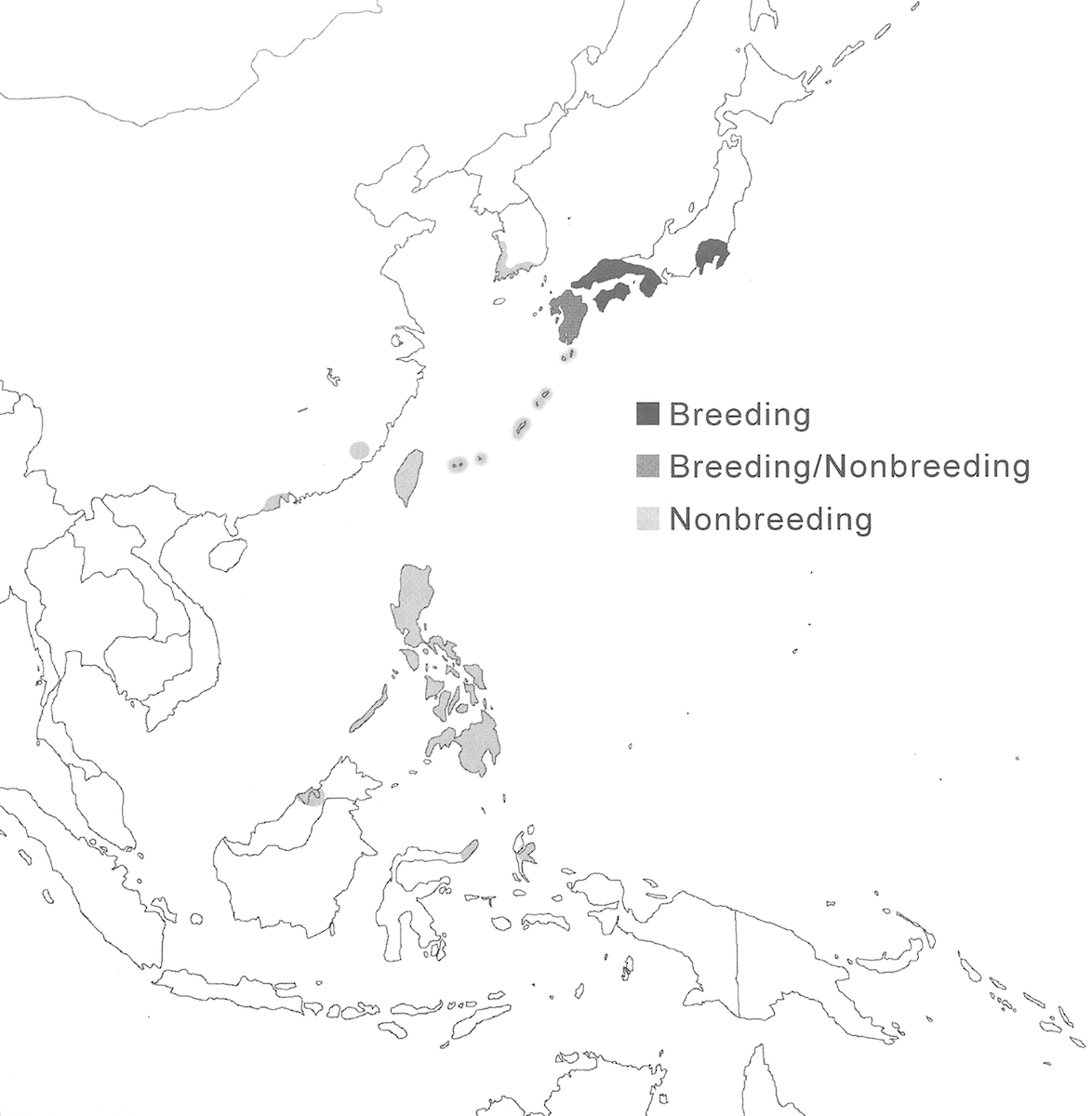

This night heron occurs in Japan, south China, and the Philippines.

Breeding range: The Japanese Night-Heron breeds only in Japan in Honshu, Shikoku, Kyusgu and on the Izu Islands.

Nonbreeding range: The overall range in spring and or summer is larger, but breeding has not been proven. It has bred in small numbers on Taiwan (Severinghaus 1989) but without recent record. Birds occur in spring and summer in east Russia (Primorye, Sakhalin) and South Korea (Gore and Won 1971). Some birds remain in Philippines in summer (Rand and Rabor 1960). These various spring and summer records suggest the possibility of breeding, but this needs to be proven.

In the northern winter, the heron occurs in south Japan (south Kyushu, Ryukyu Islands) and southeast China (Guangxi, Fujian, Zhejiang, Taiwan). Its principal wintering range appears to be the Philippines (Luzon, Semirara, Leyte, Negros, Panay, Siquijor, Mindanao, Palawan).

Migration: The Japanese Night-Heron is highly migratory. They move south at the end of October and occur widely trough Japan on passage. Some may remain in Kyushu but most move south through the Ryukas to and through China to the Philippines. Return is in March–May.

The species has some dispersal tendencies, possibly overshooting on southward or northward migration. It has occurred on Palau, Indonesia (Sulawesi, Halmahera), and Brunei (Borneo) (Elkin 1993). Given the paucity of records and difficulty of observing it, it should be sought after in these areas to determine if it might not be more regular than thought.

Status: The species is rare and extremely local in Japan. There is no population estimate available and it is not counted on surveys due to its secretive nature. Only 6 nesting sites are known (Lansdown et al. 2000). It is likely that the population numbers less than a few thousand birds (BirdLife 2001).

At the beginning of 20th century it was common and remained relatively common into the 1940’s and 1950's. It disappeared from many traditional areas in the 1980’s and 1990's. Although it was reported to have bred in Taiwan, it is now a rare as a winter visitor and passage migrant there and in south China (Sykes 1996). It is rare but regular in South Korea. It is uncommon in the Philippines, which is probably its main wintering area (Dickinson et al. 1991).

Habitat

This is a nocturnal forest heron. It is occurs in heavily forested rivers, streams, and swamps, in the low mountains. This habitat is now extremely scarce in Japan. Similar habitats appear to be used in the nonbreeding range (Sykes 1996). It occurs generally from 50-240 m in elevation, but has been reported as high as 1,500 m in Japan and 1,350 m in Philippines (with two records from as high as 2,400 m).

Foraging

The Japanese Night-Heron is primarily crepuscular, feeding solitarily or in small groups. It feeds by Walking slowly within the dense vegetation presumably along watercourses and pools but also on dry ground. It forages more rarely in the open. Habitats used include swamps, forest, farms, and rice paddies.

The diet appears to consist mainly of crabs and possibly other crustaceans, insects, earthworms, and small fish.

Breeding

The Japanese Night-Heron breeds in May–July. It nests in tall trees, 7-20 m tall. Species include cedar (Cryptomeria), cypress (Chamaecyparis), oaks (Quercus), zelkovi (Zelkova), and chestnut (Castanea). On migration in China it occurs in tall trees and bamboo forests along rivers and in the hills. The species nests solitarily. However in favorable situations these nests can be gathered within relatively close proximity (250-500 m), although not truly a colony. Nests are flimsy, crude platforms of sticks, placed on more or less horizontal and usually densely foliaged boughs, 7-20 m above ground.

Nothing is known of courtship display in this species, and little of its nesting habits. Incubating bird will adopt the Bittern Posture when alarmed. Eggs are dull white and measure on average 47.5 x 37 mm. The clutch is 3-4. The incubation period was estimated to be 17-20 days. Nothing is known about the hatching, growth, or breeding success of this species other than fledging occurs in 35-37 days. Late eggs found in July suggest renesting.

Population dynamics

Nothing is known of the population dynamics of the species.

Conservation

The Japanese Night-Heron is endangered (IUCN 2003). With only six confirmed and 15 possible breeding sites (Lansdown et al. 2000), the species is certainly under threat of extinction. If the 21 sites in Japan each supported 10 pairs, which is unrealistically high, the total known breeding population could be as few as 200 birds. It is certainly less than a thousand birds. Conservation of this species faces two great challenges: lack of information and destruction of the species’ habitat. The lack of information on the species constrains conservation action. The present status and distribution of the species must be determined as rapidly as possible. The 21 identified active and possible breeding sites should be re-examined for nesting, and those supporting nesting birds should be protected in a reserve system (Hafner et al. 2000). Threats to the known habitat of the species, both during breeding and non-breeding, are the principal conservation issues facing this species. In Japan, hill forests have been and continue to be deforested and converted to plantations. Remaining forests have developed a scrubby undergrowth (BirdLife 2001). Very little pristine forest habitat remains in Japan. Remnant stands need to be protected. Although the species is now found in degraded habitat, thoughts that this is an adequate habitat are probably incorrect. In the Philippines, lowland primary forest is similarly threatened by deforestation, rendering some areas totally unsuitable for the species. Protection of habitat on the wintering grounds is essential to the species’ conservation. Hunting may in the past have been a factor in its conservation. They have been found for sale in Taiwan in the 1970’s and Gorsachius herons have been confiscated in trade in the 1980’s. Introduced predators have led to its decline on islands.

A species action plan covering both breeding and non-breeding areas is desperately needed for the species.

Research needs

Research is difficult given the secretive nature and tenuous status of the species. None the less, much could be learned from observational study. So little is known about the biology of this species, which represents an adaptive arm of the herons—a small nocturnal upland forest heron, that its basic biology needs to be understood and related to both conservation needs and heron biology. Surveys need to be conducted to locate breeding and wintering areas. Given the apparently small population size, any site with a few birds constitutes an important area for this species. These sites need to be identified and placed in a range-wide reserve network to be monitored, protected, and managed. The taxonomy of the night herons is not well understood, and a thorough analysis is needed.

Overview

Nearly nothing is known about the ecology of this rare and declining species. In fact, it is not understood what constitutes the basic ecological characteristics of a nocturnal forest heron. It is certainly a very rare species that has depended on a forested habitat that has been under severe threat on both the breeding and wintering areas.