Malayan Night-Heron

Gorsachius melanolophus (Raffles)

Ardea melanocephala Raffles, 1822. Trans. Linn. Soc. London 13, p. 326: western Sumatra (Probably near Bengkulu).

Other names: Malay Tiger Bittern in English; Martinete Malayo in Spanish; Bihoreau malais in French; Wellenreiher in German; Zuguro-mizo-goi in Japanese; Bakaw-gabi in Pilipino (Philippines); Kowak melayu in Indonesian; Helguan yan in Chinese.

Description

The Malayan Night-Heron is a small chestnut and brown nocturnal heron of low to mid elevation wet forests.

Adult: The crown and nape are black, ending in a long black crest. The bill is stocky, down-curved, dark brown above and green below. The lores and orbital skin are blue green. The irises are green yellow. The sides of the face and neck are rufous. The chin is white with a central row of black streaks. The back and upper wings are chestnut finely barred with black. The flight feathers are brownish-black with white tips, visible in flight. The tail is black. The underparts are dark brown finely speckled with black. Flanks and undertail-coverts mottled brown and white. The legs and feet are olive. During breeding the lores become blue. The males change well in advance of nesting whereas the female’s change during courtship (Chang 2000). After courtship the lores faded to blue green, green, to grey green.

Variation: The sexes are alike, but the male may have a longer crest and bluer lores in courtship (Tsao 1998). The species shows a high degree of individual variability in plumage. Previously three subspecies differing in plumage color were recognized, but their variability appears to be within the overall range of individual variation of the species. Geographic variation does occur however. Immature birds of the herons breeding on Palawan are buff heavily overlaid with black. Herons from the Nicobar Islands are small.

Juvenile: The immature is cryptically colored, strikingly different from the adult. Upper parts are dull grey to brown spotted and barred with white and buff. Under parts are white, spotted and barred brown. The crown is blackish barred and spotted with white.

Chick: The chick has not been described.

Voice: “Arh” call, rendered “arh, arh, arh” is the flight and interaction call. It also has hoarse croaks that are not yet characterized.

Weights and measurements: Length: 49 cm, Weight: 417-450 g.

Field characters

The Malayan Night-Heron is identified by its rufous neck, barred chestnut back, black cap with crest, and white tipped primaries. The Malaysian Night-Heron is distinguished from the Japanese Night-Heron by its chestnut brown (not darker body color), Black (not tawny) crown and longer crest, slightly longer thinner bill, and white (not tawny) tips on primaries. It is distinguished from the Cinnamon Bittern by its short stubby (not long and pointed) bill, black crown, blue green lores, larger size, barred cinnamon back (not plain cinnamon or brown with buff spots), black and cinnamon wings with white flight feather tips (not uniformly cinnamon). It is distinguished from all bitterns by its white wing tips and stout bill.

The immature Malayan Night-Heron is distinguished from the immature Rufous and Black Crowned Night-Herons by its short, stubby and downward-arched bill, smaller size, finer spotting on the back and wings, and mottled (not stripped) under parts. It is distinguished from the immature Striated Heron by its slightly smaller size, spotted (not plain) back, shorter stubbier bill, and green (not yellow) legs and feet.

Systematics

The Malayan Night-Heron is closely related to the Japanese Night-Heron. The relationships among the night herons are unsettled. Patterns of individual and geographic variation as is the appropriate subspecific taxonomy need to be clarified.

Range and status

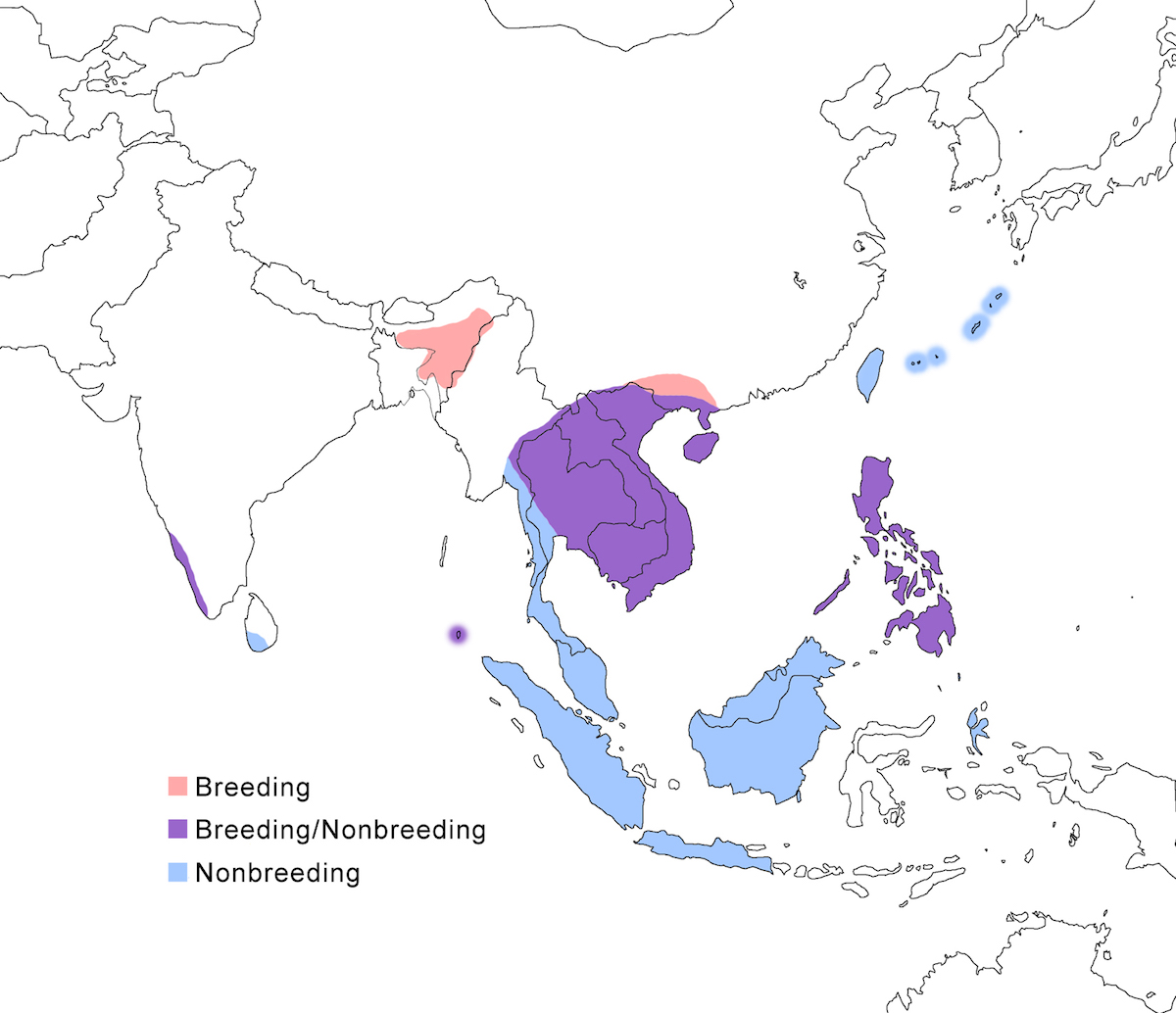

The Malayan Night-Heron occurs in India, south east Asia, Philippines and the east Indies.

Breeding range: The Malayan Night-Heron breeds in India (west India, Assam and Manipur, Nicobar islands), Nepal, Thailand (north), Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, (Cambodia not certain), south China (Hainan, Guangzhou, Taiwan – Sykes 1996, Yunan, Gaunxi, Kwangsi, Guangdong (Lansdown pers. comm.), the Philippines (including Palawan), and Japan (Ryukyu Islands). Recent information reporting immature birds in Malaysia (Peninsular, Taman Negra), Java, and Borneo suggests nesting, but this needs to be confirmed (Perennou et al. 2000, R. Lansdown pers. comm.).

Nonbreeding range: It occurs during non-breeding in west India (Perennou et al. 2000), Sri Lanka, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, south China (Hainan, Guangzhou, Taiwan), Malaysia (Malay Peninsula, Sarawak), Indonesia (Sumatra, Java, Kalimatan, Halmahara, Talaud) (Coates et al. 1997), the Philippines (to Palawan), and Japan (Ryukyu Islands).

Migration: Because of it is a solitary species in difficult habitat away from surveys and bird watchers; its migration is not very well understood. Evidence exists for both migratory and sedentary habit in most populations, including west India, Nicobar, Indochina, south China, Taiwan, Philippines (including Palawan), and south Japan. It is likely that partial migration is the rule for the species, even in northern populations such as Taiwan and India, but this needs to be confirmed. Some west India birds migrate south in November–December through Sri Lanka (which is not the important wintering ground it once was thought to be), to Nicobar, Malaysia and across the Straits of Malacca, to Indonesia. East India, north Myanmar, and Thailand birds migrate south in August–October, presumably through Myanmar also to and through Malaysia to Sumatra, Java, and Borneo. Return migration through the Malay Peninsula is in April.

Whether post-breeding dispersal occurs in unclear. Birds have been seen outside the usual range, but not very far, (Shikoku Island), Palau Island, Indonesian islands (Bandai) and Christmas Island.

Status: No data are available on population sizes. Recent information suggests that the stronghold of the eastern population is in North Thailand, Vietnam and Laos (Perennou et al. 2000). It is uncommon throughout much of its range. It is uncommon and local in both seasons in Japan (Ryukyu Islands) (Wild Bird Society 1982), uncommon in nonbreeding season in Sri Lanka (Perennou et al. 2000), uncommon in both seasons in China (mainland, Taiwan – Sykes 1996), breeds throughout the Philippines but is uncommon in both seasons, rare in nonbreeding season in Java (McKinnon 1993).

Habitat

This is a heron of mature moist forests. It occurs in dense, high rainfall, subtropical forests ranging from the low wetlands, where it uses streams, marshes, and swamps, to moderate elevations, where it uses evergreen forests, secondary scrub and reservoirs. It occurs as high as 800 m in west India, 1,200 m in Thailand, 1,800 m in Sri Lanka, and 2,300 m in east India. It uses reed beds in migration and is often reported as making use of human environments, particularly flooded rice fields, pastures, and vegetable gardens and nesting near houses.

Foraging

The Malayan Night-Heron is nocturnal, although it feeds readily crepuscularly and by day as well. It is solitary forager that feeds by Walking slowly at the edges of water, fields and other feeding areas. Most observations are of its feeding in the open, but it is likely it feeds primarily unobserved under cover. In feeding on earthworms, it Probes them from the soil (Chang 2000). Little is reported on the details of its feeding behavior. It defends itself with Forward consisting of raised crest, open wings, and stabbing at the opponent. During the day, it roosts well hidden in reed, bamboo, and other dense vegetation. The diet is little studied. It eats terrestrial food, particularly earthworks and beetles but also mollusks, lizards, frogs, rarely small fish (Shen and Chen 1996).

Breeding

It nests in May–August during the big rains in west India, May–June in Assam, April–September in Taiwan. The night heron nests in lowland forests of tall trees and bamboo, usually near or over water. It nests in trees and also in reed beds. It is a colonial nester, with 20 nests close together. It also nests solitarily. The nest is a small fragile platform of sticks, sometimes lined with leaves and grass. Nests are placed well concealed in a fork of branches in trees, 5-10 m high over the water or bare ground. It occasionally nests in reed beds. Both birds of a pair build nests.

Nothing is known of the courtship and little is known of the nesting biology of this species. It appears to be typical that juvenile birds nest while still in juvenile plumage (Chang 2000).

The eggs are chalky-white with a slight greenish tinge and a single measurement was 46 x 37 mm. Clutch is usually 3, range 3-5. In Taiwan, a second clutch is laid after the first nesting is completed. Both parents incubate, which starts before the clutch is completed. Both parents also attend and feed the young. Young birds have been reported as helping at the nest in feeding the young, an unusual behavior in herons (Chang 2000). Young fledge at 43 days. Brood reduction occurred in Taiwan, with the youngest two chicks being ejected from the nest by the first hatched chick (Chang 2000). No quantitative information is available on nesting success.

Population dynamics

Birds in juvenile plumage nest, perhaps typically (Chang 2000). The observed nesting was in the months prior to molting in to adult plumage, so the birds were probably two years old, however the sequence of juvenile molts is not known. Nothing is known about the population biology of this species.

Conservation

Populations, except that of Nicobar, are vulnerable due to habitat loss (Heinz et al. 2000). The deficiency of data on this species is a critical impediment to conservation action. No doubt its habitat, like that of other Gorsachius herons, has been reduced due to deforestation and degradation. But the habitat needs of the species are not well understood, given that it is often reported to be using human-made habitats, and on Taiwan it nests in parks and near human residences (Chang 2000). It has been proposed that the species might be an indicator of environmental quality in wet tropical and subtropical forests, but this needs to be demonstrated (Perennou et al. 2000). Given its inaccessible habitat and secretive habits, it may be that the species is much more widespread and abundant than thought, particularly if it is accustomed to human-managed habitat as now is becoming clear in Taiwan. Intensive year-round surveys need to be conducted in suitable habitat in order to determine its status in various places.

Research needs

Much of the basic biology of the species remains to be determined. Information coming out of recent observations hints that the species may be of considerable biological interest. Nesting in juvenile plumage, helpers at the nest, and multiple clutches within a season are all very unusual among herons. This is a species that could reveal new elements of heron behaviour. Range-wide, year-round surveys of its annual occupancy of potentially suitable habitat need to be carried out to provide the basis for a conservation strategy.

Overview

The situation is much like that in the Japanese Night-Heron. So little is known of this heron that much of its basic biology is speculative and it is not certain what constitutes the essential characteristics of a nocturnal low- to mid-elevation wet forest heron.