North American Bittern

Botaurus lentiginosus (Montagu)

Ardea lentiginosa Montagu, 1813. Suppl. Orn. Dict., unnumbered text and plate: Piddletown, Dorsetshire, England.

Other names: American Bittern in English; Avetoro Lentiginoso, Mirasol, Ave Torro, Yaboda Americana, Guanabó Rojo, Tocomon in Spanish; Butor d'Amérique in French; Nordamerikanische Rohrdommel in German.

Description

The North American Bittern is a stocky medium brown heron marked in grey and black with a plain rusty brown crown, white chin, and black mustache.

Adult: The crown is plain rusty brown. The bill is dull yellow, with a broad dark top line and tip. The irises are yellow. The loral area is dark with a green yellow streak with a cream buff line (called the supercilium) extending above the eye. The sides of the face are brown and a black mustache streak runs from the gape down the throat and becomes a more triangular cheek patch on either side of the neck. The throat is white with rufous streaks outlined in black shading to buff on the breast. The feather tufts, on either side of the breast, are white. The hind neck, back and upper wings are rich brown finely freckled, spotted and vermiculated with grey and black. The under wing is dark brown and flight feathers are unbarred black to dark brown and contrast with the rest of the wing. The feathered thighs are buff. Its relatively short legs are yellow green.

Variation: The female is similar to the male, averaging smaller (Azurre et al. 2000a). The species shows a high degree of individual variation that is not geographically based (Parkes 1955).

Juvenile: The young are similar to the adults but lack cheek patches.

Chick: The chicks have yellow olive down, and pink bills with black-tips. Irises are olive.

Voice: The “Boom” call is the loud booming or pumping call characteristic of the large bitterns, rendered “oong, kach, oonk”, or “pump, er, lunk” with the accent on the last note. It may be preceded or followed by a series of soft gulping sounds. The Boom Call of this species is invariably described as resembling the noise of an old-fashioned hand plump, or of hammering a stake into muddy ground, leading to two of the bird’s nicknames—'stake-driver' and 'thunder pumper'. It is lower pitched than the similar call of the South American Bittern (Birkenholz and Jenni 1964). “Kok” call is the alarm and flight call, a hoarse 'kok, kok, kok' or a nasal 'haink'. The “Chu-peep” call is the copulatory call (Gibbs et al. 1992b).

Weights and measurements: Length: 60-80 cm. Weight: 550-1,072 g.

Field characters

The North American Bittern is identified by its stocky build, medium size, brown base color with grey and black markings, plain grey buff crown, black mustache, broadly brown streaked neck and breast, and finely vermiculated and spotted upper sides. It flies rather heavily and hurriedly, using rapid wing-beats.

It is distinguished from Old World large bitterns by its finely spotted and vermiculated upper parts, smaller size, longer, thinner bill, longer neck and less stocky build, darker upper bill, browner base color, and brighter green yellow soft parts (Lansdown 2000). It is distinguished from the South American Bittern by its plain buff (black barred) crown, brown (not rufous buff) base color, fine spotted, freckled and vermiculated upper parts (not barred), smaller size, black mustache, and lower pitched Boom call.

It is distinguished from immature night herons by being larger, lighter brown, having finely freckled and vermiculated (not light spotted) back, freckled (not spotted) upper wings, contrasting wings with dark flight feathers and paler body, and faster, steadier wing beat. It is distinguished from the Rufescent Tiger-Heron by its brown (not red) neck, black mustache, and stockier stature. It is distinguished from the Bare Throated Tiger-Heron by its grey brown (not black) cap, black mustache (not grey) along the cheeks, and stockier build. It is distinguished from the Fasciated Tiger-Heron by brown (not slate black brown) color, black mustache, grey brown (not black) cap, and stockier build. It is distinguished from the immature tiger herons by its stockier build and appearance, its fine black and grey freckling and vermiculation on brown upper parts (not bold, broad black and buff banding in early juvenal plumages), general brown base color, and longer toes, and marsh habitat.

Systematics

The North American Bittern is one of the four large Botaurus bitterns, which all have streaked brown plumage, scutellate tarsi, 10 tail feathers, and a booming call. It differs morphologically from the South American Bittern and from the two Old World large bitterns (Payne and Risely 1976). It is likely more closely related to the South American Bitterns than the Old World species (Payne and Risely 1976, Sibley and Monroe 1990).

Range and status

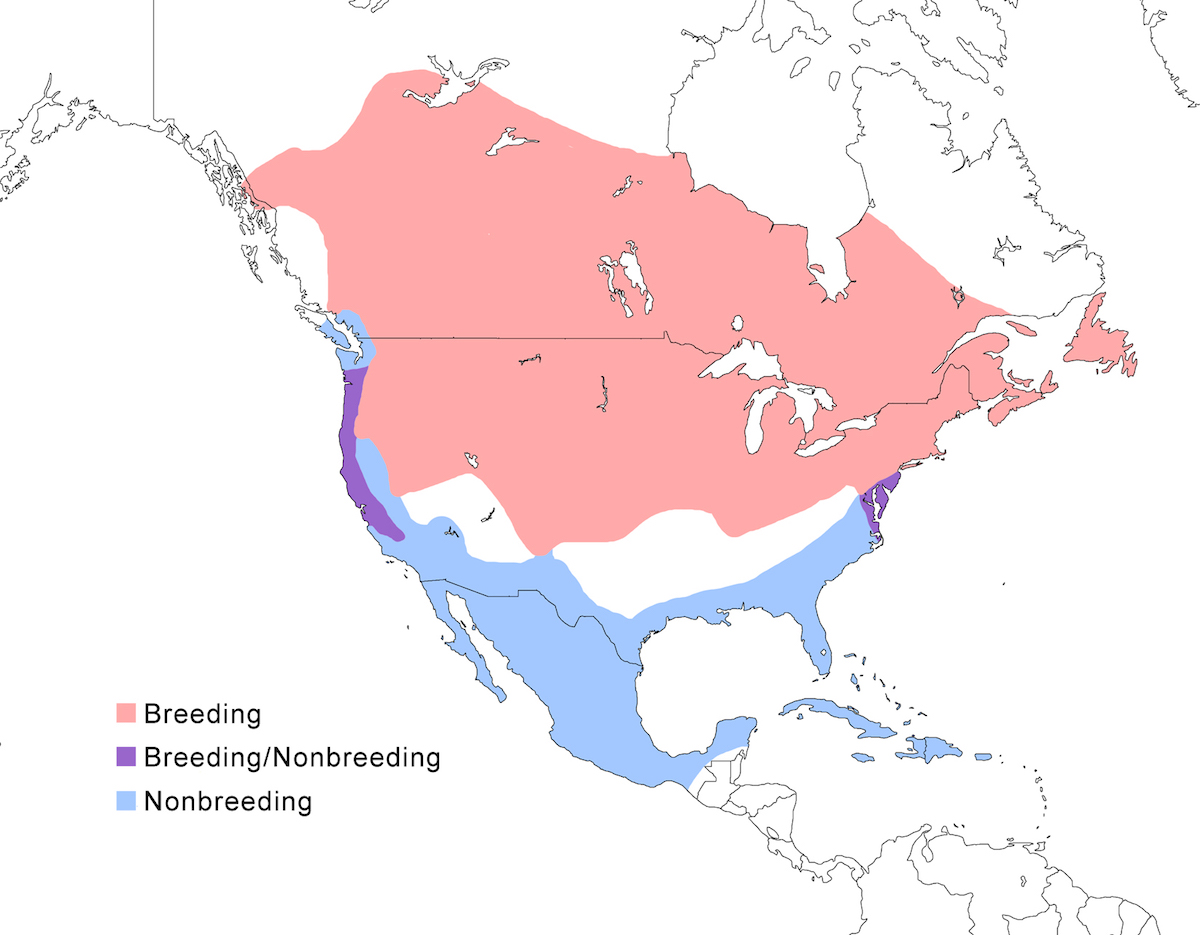

The North American Bittern occurs in North America to south Mexico, and the northern West Indies.

Breeding range: The North American Bittern breeds well north in south east Alaska, Washington, across Canada (British Columbia (55° N), Northwest Territories (at 61° N), Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, Newfoundland — Etcheberry 1990), south through all but interior United States to California, Nevada, New Mexico, north Texas, central Kansas, central Missouri, west Tennessee, west Kentucky, Ohio, south Pennsylvania, north east West Virginia, Maryland, east Virginia. It also has been recorded in the past as breeding in Florida, Arizona, Louisiana, and central Mexico (Banks and Dickerman 1978, Howell and Webb 1994).

Nonbreeding range: During the nonbreeding season, the North American Bittern occurs where waters do not freeze over, from the coastal and south United States to Central America and Greater Antilles. It occurs in British Columbia, in west coastal United States (west Washington, west Oregon, California), south and east United States (Arizona, New Mexico, Texas through Florida north to New Jersey and infrequently further north) through the Mexico and Guatemala (Land 1970), also Bahamas and the northern Antilles (Cuba, Cayman Islands, Bahamas, Jamaica, Hispaniola, Puerto Rico). Its nonbreeding status in south Mexico and further into Central America requires additional documentation. Is appears to be irregular in Guatemala (Land 1970). Although its winter range is usually noted to extend to Costa Rica, where it may have once been infrequent (Styles and Skutch 1989), and Panama, this is based on few very old records (Alvarado pers. com, Ridgley and Gwynne 1989). Additional information on status is needed from south Mexico through Central America in order to consider its usual wintering range to extend into these areas.

Migration: North American Bitterns migrate south in the northern winter to below the freeze line. Southward movement is September–November. Return is February-mid May. Migration routes are not known. Migration is nocturnal, alone or in small groups.

Extensive post-breeding dispersal also occurs starting in July. Birds occur north and south of the usual breeding and wintering ranges in Labrador, Greenland, Virgin Islands, Montserrat, Guadeloupe, Martinique, Barbados but also occurs at great distances especially on Atlantic islands and in Europe (Azores, Canaries, Iceland, Clipperton Island, Faeroes, England, Scotland, Ireland, Norway, Spain) (Brazier 1983, Madge 1983, Holt 1991, Skipnes and Folvik 1997). The bird’s occurrence east of the Atlantic is a feature of its biology. It has occurred over 60 times in Britain from 1957 to 1998 (Lansdown 2000), and in fact, the species was first described in 1813 from a vagrant specimen captured in southern England.

Status: The North American Bittern is most abundant in Canada and less so in the more southerly portions of the range (Gibbs and Martin 1992). In winter it is most abundant in the southeast United States, Florida, Louisiana, and the southwest (Salton Sea and San Joaquin Valley California). It is uncommon and local in Cuba and larger islands of Bahamas, rare in Cayman Islands, Greater Antilles, Costa Rica, and Panama.

Data suggest that a significant population decline is occurring in the United States, especially in the north central states (Hands et al. 1989). Canadian data show no downward trend. Wintering populations may be declining in Louisiana (Fluery and Sherry 1995). This trend is probably part of a long-term change of range and status, fundamentally a result of climatic amelioration with interior fresh water marshes retreating northward. Records of the early 1900’s of breeding in the southern tier of states and central Mexico and reduction in the records from Britain may all be part of this range shift northward.

Habitat

The North American Bittern is, like the other large bitterns, a bird of the herbaceous marshes, either freshwater or brackish. Although the marshland habitats of this bittern differ in detail over its extensive breeding range, they have common features of tall vegetation, shallow (5-20 cm) fresh to brackish water. Marsh plants include Typha, Scirpus, Mariscus, Sparganium, and Polygonum. It actually has a wider than expected range of habitat preferences, including coastal brackish marshes, mangrove swamps, open meadows and even relatively dry grasslands.

Foraging

North American Bitterns feed by Standing or by Walking extremely slowly. When Standing, the bird holds its bill horizontal as it watches beneath its head, moving the head very slowly, with the head and bill held low to the water. In Walking, each foot is raised slowly as the bird advances. A similar extremely slow movement is made in changing positions slightly while standing. From its low position, the bill strikes out rapidly stabbing at the prey. It can also Walk Quickly or Run, even in tall grass. It uses Gleaning to take insects from grass stems and Standing Flycatching to catch them in the air. It frequently uses Neck Swaying, often in sync with the wind.

These bitterns are very solitary feeders and have an extremely fierce looking Forward display. It crouches with wing half spread and bill forward. When another bird or other animal approaches, it quickly assumes a Bittern Posture with up-pointed bill and neck stretched out. Often it gently sways in this posture. It also uses Supplanting Flights and Supplanting runs. It defends its territory not only from bitterns but from other fish eating species as well (Phillips 1983).

They feed in shallow water, usually along the fringes of marshes and from banks along the shoreline, tending to avoid deep marsh interiors and older and overly dense vegetation. They feed crepuscularly but also during the day and at night. They daily cycle needs to be better determined.

Although this species’ food is diverse, fish dominate most diets. These include Perca, Esox, Lepomis, Ictalurus, Anguilla, and Fundulus. They also eat crayfish, snakes (Thamnophis), tadpoles and frogs (Rana, Hyla), salamanders (Ambystoma), insects (dragonflies, water bugs, water scorpions, water beetles, grasshoppers), small mammals such as ground squirrels, pocket gophers, voles and shrews, and birds such as a Sora (Porzana) and sparrows (Passer) (McBride 1993, Austin and Slivinski 2000).

Breeding

The breeding season is the spring, April–June, earlier in the south and later in the north. Eggs are laid early May in Michigan and New York, June in Quebec, May in Minnesota (Gibbs et al. 1992b).

Bitterns nest in dense cover of herbaceous marshes. They also can nest upland just adjacent to the wetland. They use both small and large marshes, although there is evidence in some areas of preferring larger tracts (Brown and Dinsmore 1986). They use various sorts of marshes such as beaver ponds, artificial impoundments, lake edges with floating and emergent plants, and especially shallow cattail marshes.

The American Bittern nests solitarily, in defended territories. Nests may on occasion be found within 40 m from one another. Calling males density figures range from 2.6 to 40/100 ha (Gibbs et al. 1992b). The nest platform is 25-40 cm. It is composed of the adjacent marsh plants and is built up from the water or lodged within the vegetation just above the water (8-20 cm). It also nests on firm ground, but nearly always in dense cover. The coming and going of the bittern makes flattened approach paths through the reeds or rushes. It is thought that the female builds the nest, but this needs to be confirmed.

The male advertises from its territory with the Boom call. It defends its sites against intruders with Forward displays, either standing or walking. In the latter display, the males approach each other in a deep crouch, erecting the white chest plumes over their backs so as to frame the head, dark crown and moustache. Supplanting flights and Aerial Fights occur, with the birds stabbing at each other. Birds also display with Circle Flights, legs dangling. The Boom call is usually given from a perch and increases in frequency as courtship proceeds.

The male probably chooses the nest site. Copulation takes place on the nesting territory, but not only on the nest, and is preceded by active pursuits. Unlike the Eurasian Bittern, evidence of polygamous nesting is slim, based on a few observations of closely spaced nests. The mating system should be assumed to be monogamous unless it is shown otherwise.

Eggs are unmarked brown or olive buff, averaging about 48.6 x 36.6 mm. The usual clutch is 4-5 eggs, range 2-7. Mean clutches are 3.8 in North and South Dakota, 4.1 in Illinois, 4.4 in Minnesota and 3.7 range wide (Duebbert and Lokemoen 1977, Graber et al. 1978, Hands et al. 1989b, Svedarsky 1992). Renesting can occur (Azure et al. 2000b). Incubation begins before the clutch is completed. It lasts 24-29 days. Incubation is by the female only, based on presence of incubation patches.

Care and feeding of young are believed to be confined to the female, but more information is needed. Chicks are fed by regurgitation. They begin to leave the nest after about two weeks. The length of time they remain dependent on the parents is unknown. Information on nesting success is very limited. Eggs hatched in only 41 of 72 upland nests (Duebert and Lokemoen 1977).

Population dynamics

There is very little information on population biology or demography. Longevity is at least 8 years (Clapp et al. 1982). It is likely that winter mortality, migration and annual reproductive success are the key demographic features.

Conservation

Canadian populations appear to be secure. But clear population declines in the central USA indicate an overall downward population trend for the species and perhaps an overall long-term reduction in breeding range. Because of its decline, it is considered to be near Threatened by HSG (Hafner et al. 2000). More and better information on status and trends are needed (Hafner et al. 2000). It is critical to identify important nesting areas and to concentrate management and protection efforts on them. Habitat management is the key to successful conservation of this species (Hands et al. 1989b), focusing on wetlands greater than 10 ha and adjacent habitat. It is probably necessary to actively manage important areas within a region to maintain mid-successional habitat for the species.

Research needs

More information is needed on the basic biology of the North American Bittern, including space use, courtship, nesting biology, success, demography, and population regulation. This information is needed to understand the causes and circumstances of long-term population and range reduction in North America. There is a need to develop more precise standard survey and monitoring methods for populations and habitats, and to use these and other techniques to assess distribution and habitat use in winter. Research is needed on case histories to develop management strategies for regionally based habitat management.

Overview

The North American Bittern is a solitary bird of dense emergent marshes. It feeds and breeds in isolation, in defended territories deep in the marsh thicket. It feeds by Walking carefully and very slowly, working its way through the vegetation, particularly near the edges of tall vegetation. It Stands for long periods and transitions to Walking extremely slowly It hunts its prey, primarily fish and insects, with great patience. Its Boom call claims its territory and advertises its personal presence. It appears to be a very northern species, not breeding over much of the usual heron range in North America. Nesting very far north, populations migrate southward in the autumn. Although somewhat flexible, it none the less depends on a few sorts of marsh habitats. Its range appears to be retreating perhaps as a response to post-Pleistocene climatic amelioration.