Purple Heron

Ardea purpurea (Linnaeus)

Ardea pupurea Linnaeus, 1766. Syst. Nat. ed. 12, p. 236: ‘in Oriente’, restricted by Stresemann, 1920, to France = ‘River Danube’.

Subspecies: Ardea purpurea manilensis Meyen, 1834: Philippines; Ardea purpurea madagascariensis van Oort, 1910: Madagascar; Ardea purpurea bournei Naurois, 1966, Oiseau 36, P. 89: S. Domingos, Ilha de Sao Tiago, Capre Verde Archipelago.

Other names: Garza Imperial in Spanish; Héron pourpré in French; Purpurreiher in German; Purperreiger in Dutch; Purpurhager in Swedish; Рыжая цапля in Russian; Cangak merah in Indonesian; Kandangaho (Pilipino), Tagak in Tagalog in (Philippins); Murasaki-sagi in Japanese; Cao lu in Chinese.

Description

The Purple Heron a very elongated, narrow-bodied heron, with long thin head and bill long neck. It is a dark grey medium heron, with orange chestnut head and neck, and chestnut breast.

Adult: The crown is black with two black lanceolate plumes up to 15 cm long. The sides of the head and neck are distinctively chestnut to orange buff to red buff. A black stripe runs across the ear to the black plumes. The long bill tapers is yellow with a horn brown top and tip. The irises are yellow. The lores are yellow green or dull green. The head and neck together are snaky. The chin and foreneck are white. Throat striping is elongated black and white spotting. A distinctive black streak runs from the eye down the side of the neck.

The back and upper wings are slate grey. Plumes along the lower back are chestnut to buff with feathers, with each feather split into several elongated and plume like tips. At rest the bird shows a deep red chestnut “shoulder” patch. The flight feathers are dark grey to black. In flight the leading edges of the wing are buff chestnut but the under wings are dark. The chest feathers are elongated into lanceolate tips that are cream white with heavy black streaky spots that merge into the black striped chestnut breast. The belly is black with chestnut stripes turning black toward the under tail.

The legs and feet are brown in font and yellow behind. Toes are elongated.

In the breeding season long scapular plumes develop chestnut buff tips. In courtship the soft parts redden, becoming orange to red.

Variation: Sexes differ. Males are larger Boev 1987b), heavier, and darker, tending to slate grey with purple gloss. The scapulars and mantle plume tips are cinnamon chestnut. Females are olive grey with buff scapular and mantle plume. Juveniles are smaller than adults. This widespread Old World species shows differentiation in base coloration and throat striping, east-west, and on islands (Naurois 1965, 1988, Payne 1979, Viosin 1991). Manilensis is paler, more grey above, and darker on the underparts, with black throat streaks more broken or absent, chest plumes whiter. Madagascariensis is darker with less obvious streaking than purpurea. Bournei is paler. The black streaks on the head and neck are conspicuous and the orange and purple is replaced by white and light rufous, but there are no size differences with the mainland African form.

Juvenile: Juvenile plumage is lighter, mainly brown above with buff edges to the feathers, more uniform buff underparts, and dark brown streaked breast. Juveniles have black crown, with a short crest but no long crown feathers or elongated scapular or mantle feathers. Stripes on the side of the head and neck are lacking. The bill and legs are dull brown, with less yellow than the adult. By first autumn, short ornamental scapulars and a few elongated breast feathers develop.

Chick: Down is sparse and hair like, rufous brown to dark brown above and white below. The upper down is tipped in white, particularly on the erectile crown. The green skin shows through the down. White tips to head down form a crest. Considerable areas on head, neck and back and belly are bare. The irises are green or yellow. The upper bill is olive green with a tinge of yellow and the lower bill is yellow with a tinge of olive green (Viosin 1991). There appears to be individual and perhaps geographical variation among Purple Heron downy chicks.

Voice: The “Frank” call is given in flight, and is higher pitched than that of the Grey Heron. “Quarr” is the alarm call. A high pitched “Quawk”call is given with the Forward display. A loud “Craak” call is used in nest relief and upward part of the Stretch. The lower part of Stretch a repeated “Clack” call or soft “Craak” call is given. Bill Clattering occurs. Food begging is a continuous “chik, chick, chick” or “ko, ko, ko, ko”. Young greet parents with a repeated “Grau-rau.”

Weights and measurements: Length: 78-90 cm. Weight: 525-1,345 g.

Field characters

The Purple Heron is identified by its long bill and neck, narrow body and wings, orange red head and neck, black plumed cap and chestnut belly. It is more often seen in flight than on land, flying to and from night roosts or breeding sites and feeding areas. In flight, it appears to be a dark, medium sized heron, with its long feet extending considerably beyond the short tail, and the long neck drooping below the horizontal (Ullman 1985, Lansdown 1985).

It is distinguished from the Grey Heron by being slimmer, smaller, darker, and in flight further distinguished by its dark wings, feet extended, kinked drooping neck, and light wing beats, the body appearing to lift on each down stroke. It is distinguished from the Eurasian Bittern by being larger, longer, slimmer, and thinner necked. It is distinguished from the Goliath Heron by its much smaller size, darker base color, orange rather than chestnut head and neck, and black crown and crest. It is distinguished from the Black Headed Heron by its orange red neck and dark upper parts. The juvenile Purple Heron is distinguished from juvenile Grey, Goliath, and Black Necked Herons by being browner, having a dark crown, chestnut neck and little wing contrast. Melanistic Grey Herons might be most confusing, but the crown, grey wing coverts, and under wing color can be used to separate them from the Purple Heron.

Systematics

The Purple Heron is clearly an Ardea, one specialized for life in reed beds. Natural hybridization has been described between Purple and Grey Herons (Campos 1990, Fenyvesi 1992). Described differences among the subspecies are primarily minor plumage color distinctions. Given the high degree of plumage and size variation within populations and between sexes and ages, additional study is needed to reassess patterns of geographic variation and assign consistent subspecific ranks, or even specific rank in the case of bournei (Naurois 1988).

Range and status

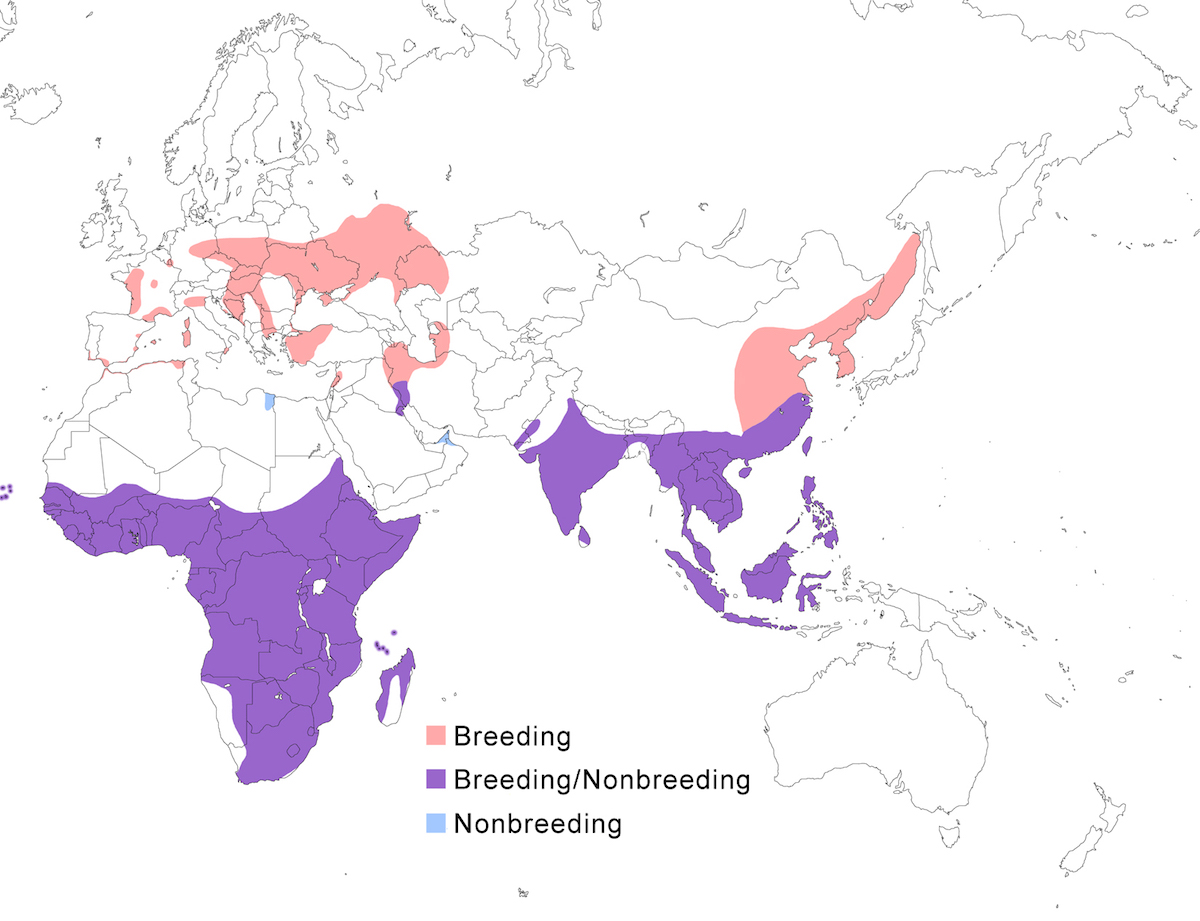

The Purple Heron occurs in temperate and tropical Europe, Africa, Asia and its islands.

Breeding range: The subspecies pupurea is the west Palearctic form, breeding from Netherlands and France, through Germany, Austria, Romania, Ukraine, Russia, to Kazakhstan, south through the Mediterranean to Turkey, Israel, Iraq, and Iran. In Africa, it breeds in north Africa in Morocco and Algeria, in west Africa in Senegal, Mali, Uganda, south Angola, in east and central Africa in Somalia, Kenya, north Namibia, Botswana, Zambia, Malawi, Mozambique and Zimbabwe, and in South Africa as far as Cape Province. Bournei breeds on Santiago Island in the Cape Verde Islands. There is distribution gap between east Europe and Pakistan. Manilensis breeds south of the Himalayas from Hindu Kush in Pakistan, India, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bangladesh to eastern China (Kwamgtung to Shensi, Szechwan, Yunnan, Hainan and Taiwan) and Russia (Ussuriland). It occurs south through Myanmar, Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Philippines. Madagascariensis is confined to Madagascar and the Seychelles Islands.

Nonbreeding range: The west Palearctic population winters occasionally within its breeding range, in extreme south Europe and the Middle East (Bahrain) and in north Africa, but most winter in Africa south of the Sahara from west Africa perhaps south to west central Congo to Sudan. The Mesopotanian marshes of Iraq and Iran have long been wintering grounds (Perennou et al. 2000). Northernmost populations of the eastern race, malinensis, also migrate joining non-migratory populations in south east China, Korea, Taiwan, Japan (Ryuku Islands), Pakistan, Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia to the Lesser Sunda Islands.

Migration: After nesting, northern populations (pupurea) birds, especially juveniles, disperse from the colony site. The west Palearctic population migrates south as early as July continuing through October (Voisin 1991). In east Europe movement from colonies also begins in July and migration is completed by early September (Knysh and Sypko 1997). Birds migrate along a braod front. Extreme western European birds follow the Atlantic coast to Spain while western birds move to Italy (Voisin 1996). From there, they cross the Mediterranean by the shortest routes. Once in North Africa both groups follow the coast west and south to west Africa. Eastern birds move along Greece and Turkey through Egypt and Eritrea. In the spring, western birds fly to the Niger River and then cross the deserts to reach south Europe directly. Migratory birds from Russia and north China move south to Korea, Thailand and Malayasia (McClure 1974). Most African and south east Asia breeders are sedentary. Migration generally occurs by day in small groups, but up to 350-400 birds have been reported in Turkey. Return migration to east Europe in the first half of April (Knysh and Sypko 1997).

Some malinensis that breed north of the Yangtze River move across Korea to Japan (Viosin 991). Bournei is not migratory. Madagascariensis appears to be sedentary or undertake local movements within Madagascar, however the possibility of migration of individuals to Africa should be examined (Viosin 1991).

Birds regularly occur outside the breeding range, often in spring as a migration overshoot. Birds occur in Britain, south Scandinavia, Atlantic islands from Iceland (Petersen 1985) to Canaries, and across the Atlantic to Fernando de Noronha and Brazil (Teixeira et al. 1987, Nacinovic and Teixeira 1989). In Asia, birds occur in central Siberia, Japan, and Korea. In Britain, visitation is an annual phenomenon in some years exceeding 30 birds (Fraser et al. 1999).

Status: The population in Europe is relatively large, 49,000 to 105,000 pairs, but only 9-14,000 pairs are outside Russia (Marion et al. 2000). The species increased its population and expanded its range in north Europe during the last century, especially into Germany and the Netherlands. However, a downward numerical trend occurred since the 1970’s across west and east Europe, with a few countries as exceptions (Tucker and Heath 1994, Marion et al. 2000). The Dutch population is now isolated. In Russia the expansion of in the 1970’s proved short term (Knysh and Sypko 1997). The Spanish population in the Ebro Delta dropped from 1,000 pairs in the 1970’s to about 60 in early 1970’s recovering to 400 by the 1990’s (Gonzalez-Martin et al. 1992). The recovery in Spain was continuing into the 1990’s (Bergerandi et al. 1995). In Mediterranean France, a decline from the early 1980’s was reversing in the mid 1990’s (Deerenberg and Hafner 1999).

There is little population data for Asia and Africa. The population in the Cape Verde Islands has decreased to as few as 20 breeding pairs from an estimated 75 pairs (not 200 as early reported) (Summers-Smith 1984, Hazevoet 1992). A population estimate for Tanzania is 5,000-10,000 birds, but it is difficult to count (Baker and Baker in prep.). It is common in scattered locations in Asia, 5,000 pairs in Zhalong China in 1980, 1,000 at Thale Nol in Thailand, and 4,000 at L Tempe in Sulawesi, Indonesia.

Habitat

This is a reed swamp heron. It prefers dense, emergent, freshwater, flooded reed or sedge beds. In Europe, low water level in the spring is the most important factor limiting occupation of a reed bed by Purple Herons (Barbraud et al. 2001b). It is seldom seen far from well-flooded marshes. It particularly feeds in shallow water with sandy or muddy bottom, among or adjacent to emergent reeds, and on and in floating vegetation. In some areas such as Europe, it may be considered a Phragmites swamp specialist, but it also uses other emergent plants, such as papyrus.

Over its wide range wide its habitat needs are a bit more generalized. It also uses mangroves, rice fields, man made ditches, canals, pools, lake shores, river edges, brackish water lagoons, and coastal mud flats. Rice fields are used when the rice is tall. Outside the breeding season it occurs more often in open habitats such as river and mud flats. It occurs from sea level to up to 1,800 m. Bournei is rather exceptional among Purple Herons, using dry hillsides and nesting in rubber trees and mango trees (Viosin 1991).

Foraging

Its feeding ecology is fairly well known (Tomlinson 1974, Rodriguez and Canavate 1985, Fasola 1986, Moser 1986b, Fasola et al. 1993, Gonzalez-Martin et al. 1992, Campos and Lekuona 1997, Knysh and Sypko 1997, Grull and Ranner 1998, Martinez Abrain 1999). The Purple Heron feeds during the day, particularly in the morning and evening. It feeds solitarily by Standing in water within dense emergent vegetation. It generally fishes in relatively deep water, up to its legs or even belly feathers. It assumes a horizontal posture and stares into the water for long periods with its bill kept close to the water surface.

It also Walks very Slowly with a methodical gait, carefully placing its very long toes on the emergent or floating vegetation. Birds do on occasion use more active behaviors, Feet First Diving (Voisin 1991). It more rarely feeds in meadows and fields stalking rodents. It typically defends individual feeding territories, especially when energy demands increase during nesting (Singh and Roy 1995).

Foraging success depends on patterns of prey availability within feeding sites. It strikes at fish capturing them crossways in a scissor grip. Its feeding appears to depend heavily on cover and it rarely leaves the cover of the reeds. It feeds most often crepuscularly, resting during the day and night, traveling to roosts singly or in small groups. They assume Bittern stance, using its camouflage plumage to good effect.

The Purple Heron feeds principally on small to medium fish (Esox, Cyprinus, Tinca, Abramis, Scardinius, Perca, Anguilla, Acerina, Lota, Mugil), although the overall range is greater, 2-55 cm long. In the south of France the most important prey and their most frequent sizes were carp (Cyprinus) (2-5 cm), mullet (Mugil) (4-5 cm), and eels (Anguilla) (25-35 cm) (Moser1984). It is highly adapted to be a marsh fish catcher, which account for the preponderance of fish in its diet (by biomass) (Campos and Lekuona 1997). It secondarily eats invertebrates, including insects (beetles, dragonflies, bugs), spiders, crustaceans (Varuna), and mollusks. It also eats frogs and salamanders (Pleurodeles, Pelobates, Xenopus), lizards, snakes (Natrix), small and juvenile birds (Fulica, Tachybaptus, Rallus, Anas), and mammals, A dietary shift from the predominance of fish (by biomass) to insects has occurred in southern France over a twenty year period (Barbraud et al. 2001a). The causes are unclear but may include changes in fish availability due to competition with the increasing Grey Heron population.

Breeding

The Purple Heron is a widespread species, whose breeding has been studied in several areas (e.g., Kral and Figala 1966, Tomlinson 1974, 1975, Moser 1984, 1986, van der Kooij 1991, Gonzalez-Martin et al. 1992, Berthelot and Navizet 1993, Thomas et al. 1999). Its basic breeding biology is known, although much remains to be understood.

In Europe and north Africa, breeding is mainly in spring, peaking in April–May, starting a month earlier in the south than the north. In north Asia, breeding is in summer, June–October. Further south breeding depends more on the rainy season cycle. For example, they breed November–March in south Asia to east Java, but February–August in west Java. In Africa, breeding is mostly in the rainy season but in some places in the dry season (e.g., peaking in April–May in east Africa and September–October in South Africa). In western Europe, the time of nesting has sifted from the third week in April to early May from the late 1970’s to late 1990's, suggesting that birds need more time to initiate nesting in more recent years due to habitat degradation (Barbaud et al. 2001a).

Nest typically over water in dense marshes and reed swamps, Phragmites swamps in temperate areas but also other emergent plants (Typha, Scirpus, Papyrus). It nests preferentially in tall reeds, so it uses reed beds that are at least a year old. When reeds are not available. it nests more frequently in trees, bushes or thickets in Asia and Africa, and also in Netherlands and France. Bournei in Cape Verde nests in tall trees.

Nesting is often in small, loose groups, especially in temperate reed swamps. But it also nests solitarily or in medium to large colonies of up to 1,000 nests in tropical areas. It nests in both single species and mixed species groups, often on the periphery of Grey Heron colonies (Knysch and Sypko 1997). Colony size depends on marsh area, particularly in reed beds of fewer than 30-40 ha. (Moser 1984, Broyer et al. 1998, Barbraud et al. 2001b).

Nests are made of reed stems or sticks. The base is made by bending over the reeds to form a platform onto which the sticks or other reeds are firmly positioned. Nest are about 36 cm wide (15-76 cm) and 18 cm thick (100-46) and are added to throughout incubation. In Europe, the Purple Heron nests low, lower than expected on the basis of its size (Fasola and Alieri 1992a), 1-3 m above the water. When they nest in thickets or mangroves, nests are higher, 3-4 m. When nesting in trees, they are up to 25 m.

Male chooses the nest site and displays there. Aerial chases and Circle Flights are not uncommon in the early stages. These can result in fights taking place in the air. Courtship displays are not well known in this species due to the difficulty in observing them. The Fluffed Neck, Upright, and Forward displays with the Quawk call are used as antagonistic displays. The Stretch display, during which the gular region is distinctively puffed out, is a greeting display in this species. In this the Purple Heron differs from other herons in which the Stretch is primarily a male courtship advertising display. During the upward part of the Stretch the Craak call is given and in the lower part a repeated Clack call is given.

Several greeting Displays are used. In one the returning bird utters the Craak call as it lands away from the nest. The brooding bird turns away from the approaching bird, an unusual response among herons and gives a Stretch display. The incoming bird stands upright with neck feathers erect. Another Greeting Display used in nest relief consists of the brooding bird bowing its head with tail up, followed by the approaching bird lowering its head. A more complex elaboration of this greeting display, not seen in other species, has been described as a Sway and Bob display (Tomlinson 1994, Viosin 1991). Upon being approached, the brooding bird bent forward, head down, tail up, swaying from side to side, and then rapidly bobbed tail and head up and down, before returning to swaying. Allopreening with Bill Clappering and Back Biting are common between the pairs. Upright and and Bittern stances are used upon disturbance.

The eggs are pale blue-green. In Spain they are 55.2 x 40.4 mm; in South Africa 55.4 x 39.5 mm; in Asia 54.6 x 39.7 mm. Eggs are laid at 1-3 day intervals. The clutch size 2-8, varying regionally (Moser 1986a, Gonzalez-Martin 1992), for example 5.3 in Hungary, 5.1 in Spain and France, 5.7 in Russia (Knysch and Sypko 1997), 3.2 in Zimbabwe, 2.9 in Botswana and 2.5 in South Africa. Usually a single clutch is produced per year, but replacement clutches can occur (van der Kooij 1997).

Eggs are incubated 25-27 days by both parents beginning with the first egg. A Greeting Display between nesting birds involves a Stretch by the incubating bird turning away from the arriving bird, a unique posture in herons. The chicks hatch asynchronously. Over 95% of eggs in a Russian study hatched (Knysch and Sypko 1997). Nestlings are attended and fed by both parents, at first on food regurgitated on the floor of the nest, and later on whole items taken from the parent’s bill.

Sibling rivalry can be intense and later chicks (5 and usually 4) do not survive. The young begin to clamber from the nest at seven to ten days. The first and second chicks grow more rapidly than subsequent chicks in the brood. In a study in south France, the fourth chick at first grew slowly before speeding up, after its older siblings were no longer in the nest. At three weeks they spend most of their time out of the nest. At least another three weeks are required before they are fully fledged, and they become independent two weeks later.

Many predators can take chicks, including otter (Aonyx), harriers (Circus), crakes (Limnocorax) and monitor lizards. Nests can be lost to strong winds (van der Kooij 1997) and also fails if water levels drop rapidly at the colony site, even if it does not dry completely. Nests can be flooded by water level rising too high during nesting. In Africa nesting success was 27% of eggs laid. Survivorship was greater in Spain. Survival of an egg to 16 days was 68%, and survival of a hatched chick to 16 days was 99%. In Russia broods averaged 5.36 young per nest (Knysh and Sypko 1997).

Population dynamics

Survival in migrating populations is affected by conditions on the wintering grounds (den Held 1981, Cave 1983). Variation in breeding birds is caused by variation in survival of older than first year birds related to the severity of drought conditions in the wintering area in west Africa. Migration deaths also occur (Nikolaus 1983), and it is possible that most mortality of first year birds may occur before they reach the wintering grounds (Cave 1983). In one study, over 60% of birds found dead were in their first year. Recent analyses have shown that both conditions on the breeding ground and conditions on the wintering grounds (rainfall in the Sahel) affect the size of the breeding population (Barbraud and Hafner 2001). The oldest known wild Purple Heron was over 23 years old.

Conservation

Purple Herons are scarce and localized through west Europe because their reed bed habitat is scarce (Hafner 2000). The population decline there has been underway for decades, as reed beds have been lost to development, water management practices, cane harvest (Jongejan 1986, Thomas et al. 1999), or elimination for other purposes, e.g. to reduce sedimentation (Broyer et al. 1998). This is a bird that is sensitive to disturbance and highly dependent on a specialized habitat and food resource. As a result, it is susceptible to many sorts of feeding and nesting habitat alteration working in combination (Deerenberg and Hafner 1999). Because of this, it is considered to be regionally vulnerable in Europe and north Africa (Hafner et al. 2000). Reed bed management for conservation is essential to the well-being of the Purple Heron in west Europe. Unfortunately, commercial reed harvest continues to be detrimental to Purple Herons despite European subsidies aimed at protecting heron colonies (Barbraud and Mathevet 2000). Overall Purple Heron conservation is favoured by maintaining large uncut reed beds with relatively high spring water levels (Barbraud et al. 2001b). Purple Herons also have a history of being killed by humans, either by shooting or by fences and other obstructions. The species has been protected since 1975 in France and 1981 in Spain, an essential aspect of its population recovery during that period (Voisin 1991). Population monitoring needs to continue, additional information is needed on habitat requirements and management, and reed beds need to be monitored and protected. This is a population potentially at risk because of conditions on the wintering ground, about which little is known.

The population of Purple Herons on Cape Verde may be down to 20 pairs. This isolated population is globally threatened and requires immediate conservation action (Hazevoet 1992, Hafner et al. 2000). This seems to be a Purple Heron of a different sort, apparently independent from wetlands and nesting in a few tall trees. There is no information on habitat use and limiting factors for these birds for most of the year. The reasons for the population decrease and needed conservation measures are not clear. But the current colony sites need to be protected, a survey undertaken of other possible sites, and a conservation plan for this population needs to be developed immediately.

The species is widespread and common over the rest of its range and is not of immediate conservation concern there.

Research needs

The most critical research need is to better understand the ecology of Purple Herons, particularly the relationships of reed bed characteristics to heron use and reproductive success. Information is needed on the distribution, habitat use, winter mortality, and environmental limiting factors in the wintering range on European birds, in sub-Saharan Africa. Study of the geographic variation within the species is desirable, both because of its widespread and disjunct populations and also as a basis for conservation action. Morphological and biochemical study is needed across its range, especially for the threatened population on Cape Verde and the island population of Madagascar. The biology of this species, although well studied, may hold additional surprises. The suggestion that competition for food during nesting with increasing Grey Heron populations has affected population sizes needs to be studied further. The reported high variation in weight, possibly based on food intake (Voisin 1991), suggests profound adaptations for variable food supplies. Recent evidence on the role of spring water levels and further clarification of the relative roles of ecological roles on the breeding ground vs. wintering grounds also deserve further study.

Overview

The Purple Heron is a bird adapted to and dependent on a very specific habitat––dense reed beds. Its long toes, short tarsus, thin body and head, and long bill can be seen as adaptations for living in this habitat (Boev 1988a). It feeds by solitarily waiting patiently for prey or by Walking slowly over and through the reeds. It is also a diet specialist and is among the most morphologically specialized of European herons for fish eating (Boev 1989). Together, these characteristics indicate that it has among the narrowest of ecological niches of the typical herons. Although still an abundant species through much of its range, the Purple Heron’s specialization has rendered it vulnerable to habitat alteration, especially drainage and commercial reed harvest. It has responded by population declines, shifts in colony size and locations, changes in prey consumption, and shifts in its annual phenology. It is also affected by hydrological conditions on its wintering grounds, which can affect population size in the following breeding season.