Slaty Egret

Egretta vinaceigula (Sharpe)

Melanophoyx vinaceigula Sharpe, 1895. Bull. Brit. Orn. Cl. v, p.xiii: Potchefstroom, Transvaal.

Other names: Red-throated Heron, Brown-throated Egret in English; Garceta Gorgiroja in Spanish; Aigrette vineuse in French; Braunkehlreiher in German.

Description

The Slaty Egret is a medium pale grey heron with a red to brown throat, highly localized in the swamps of central south Africa.

Adult: The base color of the Slaty Egret is a pale blue grey, including head, side and back of neck, back, tail and wings. The bill is narrow, black with a pale keel to the lower bill. The irises are pale yellow, set off by a fringe of black feathers. It has a red brown chin, throat and foreneck. Narrow grey crest plumes extend from the back of the head, lower neck and back. The chest plumes are mixed with red. The back plumes extend beyond the tail and are conspicuously curved at their tips. Its abdomen and flanks are black mixed with red. The under wing is buff and pale blue grey. The legs are dull grey yellow to yellow green. Toes are small ranging from pale to bright chrome yellow. The red throat tends to buff over time.

Variation: Females may be smaller than males. Individuals vary considerably in the amount and distribution of red brown on the throat as well as in leg and feet color (Hines 1992, Hustler 1995).

Juvenile: The immature bird is a pale slate grey with the upper throat and breast buff pink to pink brown sometimes extending down to the belly; the tarsus is grey green and there is no crest.

Chick: The chick has black purple down above, pale grey below. The skin is pink to yellow turning green grey. Throat is yellow to orange yellow. Bill is horn to pink, black brown toward tip. Legs are pink to yellow orange turning green.

Voice: A triple “Kraak” is the agonistic call. Other calls have not been reported.

Weights and measurements: Length: 43 cm. Weight: 250-340 g.

Field characters

Although the throat coloration is unique, it is not always easy to see. The Slaty Egret is distinguished from the Black Heron by its slighter, thinner posture, red throat and yellow legs (Beel 1993). It is distinguished from a dark Little Egret by its throat color, its slender neck and bill and yellow legs.

Systematics

One of the least known herons, the Slaty Egret has been a taxonomic mystery (Bock 1956, Benson et al. 1971, Vernon 1971, Irwin 1975, Payne and Risely 1976). It was first described from South Africa as a new species resembling the Black Heron but with a vinaceous not black throat. Lacking additional specimens, the consensus grew that these birds were a color phase of the Black Heron. However, the Slaty Egret’s morphology, habitat requirements and feeding behavior differ markedly from the Black Heron and the taxonomy of this species was clarified in the 1970’s.

Range and status

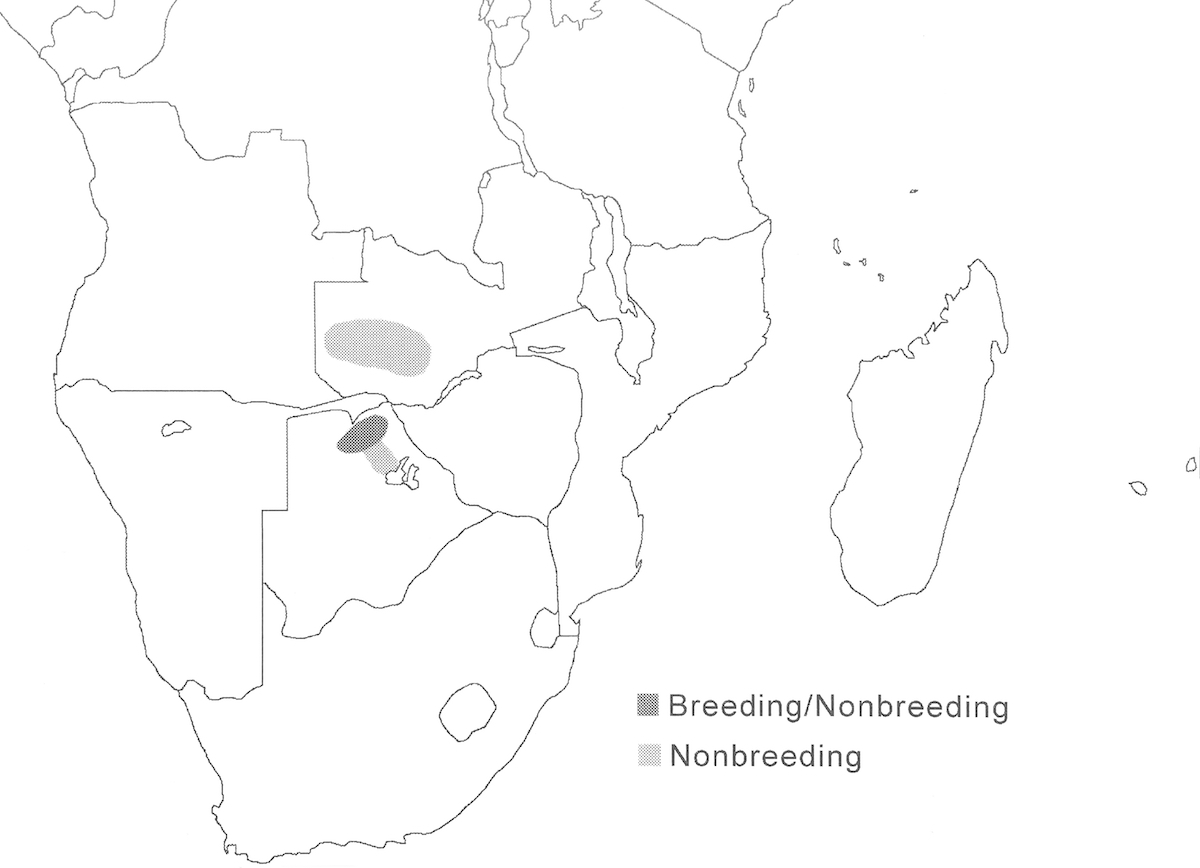

The Slaty Egret has a small overall range within the great flood plain wetlands of south central Africa.

Breeding range: The overall breeding range includes north Botswana, north east Namibia, north west Zimbabwe, Zambia (Kafue flood plains, Bangweulu swamps), north South Africa, possibly south Zaire and east Angola, Malawi and Mozambique. Currently breeding is known from only a few sites in Botswana (Chobe and Okavango), Namibia (Caprivi), and South Africa (Nye flood plain) (Tarboton 1996). But it is likely to breed elsewhere within the larger range and probably was overlooked during the period when it was considered to be the same species as the Black Heron.

Migration: Birds are resident year round in some locations, for example along the Zambezi in Caprivi, and along Linyanti and Kwando rivers. In other places, birds undertake seasonal movements associated with changing feeding conditions due to rainfall and flood stages.

Status: This heron is widespread in the core of its range in north Botswana but patchy and uncommon elsewhere within its restricted range. The world population must be small, the breeding pairs actually counted in colonies are fewer than 100. Its population size is very poorly documented, but must be fewer than 5,000 birds.

Habitat

The Slaty Egret is a bird of seasonally fluctuating wetlands associated with flood plains of large rivers. It feeds generally in small shallow pools, along the margins of small channels, along floating vegetation mats, in temporary shallow pans, and temporary pools flooded by rainfall. It prefers to be in and near vegetated areas and uses open water sparingly. It typically uses an area as water levels decrease from the peak of the wet season.

Foraging

The Slaty Egret is an active forager in shallow water, generally less than 10 cm deep (Milewski 1976, Mathews and McQuaid 1983, Hines 1992). It feeds by Walking Slowly, stalking and then stabbing at prey. It also Stands and waits for prey, typically using foot moving behaviors (Foot Stirring, Foot Probing, Foot Raking, and Foot Paddling). Foot stirring is used up to a quarter of the feeding time. Standing and Walking Slowly are particularly used at dawn and dusk when fish are surfacing. It uses more active behaviors when fish are less available, mid day. It Walks Quickly and Runs short distances after prey with partly open wings. It Gleans snails from lily pads, uses Standing Flycatching to dragonflies, and Probes. It also uses sticks to attract fish (Hustler 1995).

It feeds solitarily, in pairs or small groups usually of a few birds but up to 30 have been observed. It associates in mixed assemblages with other herons and waders. When feeding in groups, feeding sites are defended and aggressive encounters include chasing other birds for many metres. It is a diurnal forager, particularly active at dawn and dusk. It roosts in trees and thick reed beds.

Slaty Herons eat small fish (5-10 cm), and also snails, dragonflies, dragon fly larvae, tadpoles and frogs. In that no fish occur in temporary wetlands, insects and tadpoles comprise the diet in this situation.

Breeding

Few nesting sites have been reported or studied so the breeding biology is little known. The birds’ flexibility in nesting and feeding is only beginning to be understood (Matthews and McQuaid 1983, Fry et al. 1986, Hines 1992, Randall and Heeremans 1994). It nests in March–June, at or just after the height of flooding in both river flood plains and temporary wetlands (Hines 1992, Randall and Heeremans 1994).

Nests in bush thickets of Ficus or Acacia and in large stands of mature reed beds (Phragmites australis). Nests in small colonies, perhaps typically with Rufous Bellied Herons. Nests reported at sites were 1, 8, fewer than 30-50, and about 50-60. Nests are made of sticks or reed. They seem typically to have extensive soft grass and sedge lining, but some reported did not. Vines may be important nest components. Variability may be due to nesting materials being collected very near to the nesting site. Nests are 30-40 cm wide and 10 cm deep, with as shallow central depression. They are placed 1-5 m above the ground, lower in reeds than in shrub.

Nothing is known of the courtship behavior of this species. Eggs are pale blue green. They measure 39-45.9 x 29.5-32.6 mm. Clutch is usually 3 (2-4). Incubation is estimated to be around 21-24 days. There is little information on chick rearing stages. Nesting success appears to be low, about 8% of eggs to fledging in one study, 30% in another. Predation risk appears to be high. A colony in Namibia failed due to a pair of eagles (Haliaeetus) and other predators are implicated in other nest failures. In a central Okavango colony, predators killed not only young but also adults. Young leaving the nest die of accidents, such as being impaled by or stuck in the reeds.

Population dynamics

The population biology of this species is unknown.

Conservation

This is a highly restricted species that is at risk to habitat alterations within the wetlands it inhabits. The species uses mature reed and bushy thickets to nest. Fire, reed cutting, drainage, agricultural conversion, and water diversion all threaten these habitats. Birds were eliminated from parts of the flood plain after the Kafue River was dammed. Birds abandoned a reed colony site after it burned. The proposed development of rice farming in Caprivi will alter the Zambezi flood plain. Livestock grazing can impact reed beds. Proposed water diversion and management in the core of its breeding range in the Okavango would be catastrophic for the species. Specific threats include water removal from the Okavango River for urban and agricultural use and the Popa Falls dam in Namibia (S. Tyler pers. comm.). It is considered to be Endangered by the Heron Specialist Group due to it small global population size and restricted habitat that is under multiple threat (Hafner et al. 2000). It is considered to be Vulnerable by the IUCN (IUCN 2003) due to habitat loss and degradation. A conservation Action Plan is required for this species. The most important immediate activity is to carry out thorough surveys to locate nesting sites and then to identify and protect important areas. With a likely world population of probably fewer than 5,000 birds, sites with 25 nests would be classified as important wetland areas. Important nest sites need to be protected and managed, for disturbance, habitat alteration, and development threats. Development plans in the wetlands it occupies need to be evaluated for potential impact and altered as needed to protect this species.

Research needs

The typical habitats of this species, namely reed beds in extensive shallow inundation zones and temporary rainfall basins, are a not uncommon situation on many African river systems. So why this species, which has some ability to move about, has such a restricted distribution is unclear. Further study of the breeding and feeding biology of this species relative to water fluctuations and specific nesting habitat requirements is needed. The apparent low nesting success and vulnerability to predators need to be better understood in order to assess their true impact.

Overview

The Slaty Egret appears to specialize in some utilizing drying conditions, and as such shows some degree of adaptability as suggested by its diverse foraging behaviour and opportunistic population shifts. Its known colony sites are used when water levels are falling, and nesting is abandoned when drying is delayed. The birds shift seasonally to take advantage of appropriate water conditions, assemble in mixed aggregations to use stranded fish, and even move to breed in places where water levels are temporarily or intermittently suitable. In the river flood plains, drying conditions concentrate fish. In temporary wetlands, invertebrates and tadpoles are taken. But the pattern is consistent-birds utilize a place when food is made available by fluctuating water levels.