Squacco Heron

Ardeola ralloides (Scopoli)

Ardea ralloides Scopoli, 1769. Annus I Historico-Nat., p. 88: Carniola (formerly Austro-Hungarian Empire now Kranjska in Yugoslavia).

Other names: Garcilla Cangrejera in Spanish; Crabier chevelu, Héron crabier in French; Rallenreiher in German; Ralreiger in Dutch; Жёлтая цапля in Russian.

Description

The Squacco Heron is a tawny buff brown heron with a streaked head and back, and in breeding a black and white mane.

Adult: The adult nonbreeding Squacco Heron has a head that is finely streaked in black, brown, and grey, forming a modest crown but no elongated plumes in nonbreeding season. The relatively large and powerful bill is pale green yellow with a black tip and top. The lores are dull yellow green. The irises are yellow. The hind neck, like the head, is finely streaked in black, brown and grey. The upperparts are buff brown with slight tawny tinge. The wings are white and are mostly concealed at rest by the back plumes. The plumes are shorter than in the breeding season. The rump and tail are white. Foreneck and breast are bright buff coarsely streaked in dark brown. The remaining underparts are white. The relatively short legs and the feet are dull yellow green.

In breeding plumage, the upper parts become brighter and deeper. The crown is a mane of yellow buff or straw-colored feathers. The crown feathers are slightly elongated (1-5 cm) and are bordered with black. Several very elongated feathers (13-14 cm long) occur on the back of the crown. These are white bordered with black, and extend over the upper back. The lores are green or blue. The lower neck and back plumes are golden to cinnamon buff. The foreneck and breast are red gold. During courtship, the bill becomes bright blue except for the dark to black tip. The lores turn briefly blue before reverting via emerald to yellow green. The irises in courtship are richer yellow. The back is pink brown, with longest back feathers being golden and drooping over the wings. The legs are bright red in courtship, fading to pink after pairing. The other soft parts colors return to normal after the eggs are laid.

Variation: The sexes are alike. Geographic variation is not recognized taxonomically. South and central African birds were once considered recognized as the subspecies paludivaga.

Juvenile: The immature bird is similar to adults in nonbreeding, but drabber. It lacks the crest and back plumes. The bill is more uniform with a dark tip. The breast is more strongly streaked in dark brown. The underparts are grey rather than white. The flight feathers have a brown tinge and shafts, so that the wings appear to be mottled with brown. The tail also is washed with brown tint.

Chick: The chick has dark grey down, with long brown grey down on the head forming a crest. The irises are yellow and lores green yellow. The rest of the skin is olive green. The bill is yellow with a dark tip. The belly is naked for the first two weeks. Legs are olive green in the front and pale yellow behind.

Voice: The Squacco Heron is generally a quiet bird. The characteristic “Squawk” call, rendered variously as “caw”, “kak”, ‘rrra”, or “kak”, is given often at dusk, especially during breeding, as part of the Forward, and in flight. The call becomes a “kek, kek, kek, kek” in an aggressive Forward. “Grr” call, rendered “grrrr, grrrr, grrrr, grrrr”, is the alarm call. The young beg with “kri, kri, kri, kri”.

Weights and measurements: Length: 42-48 cm. Weight: 230-370 g.

Field characters

The Squacco Heron is identified by its tawny buff brown color, streaked head in nonbreeding and its crest during breeding. It flies rapidly with rapid wing beats, its white wings contrasting with dark body forming an important field character, especially upon take off. When feeding, it appears as a small solitary brown buff heron.

Juvenile and nonbreeding birds are difficult to tell from other pond herons, as is the juvenile. It is distinguished from the Indian Pond-Heron by its head streaking (vs. no streaking). In breeding it is distinguished from the Malagasy Pond-Heron by its tawny not white plumage. It is distinguished from the juvenile Malagasy Pond-Heron by being more slight, tawny (not dark) plumage, lighter streaking, slighter bill, and narrower wing tips. It is distinguished from the Cattle Egret by its slender build, darker back, white wings, darker (not yellow, orange or red bill) and streaked head.

Systematics

The Squacco Heron is an Ardeola, closely related to the other pond herons. Four of the pond herons (Indian, Javan, Chinese and Squacco) are considered to form a super species.

Range and status

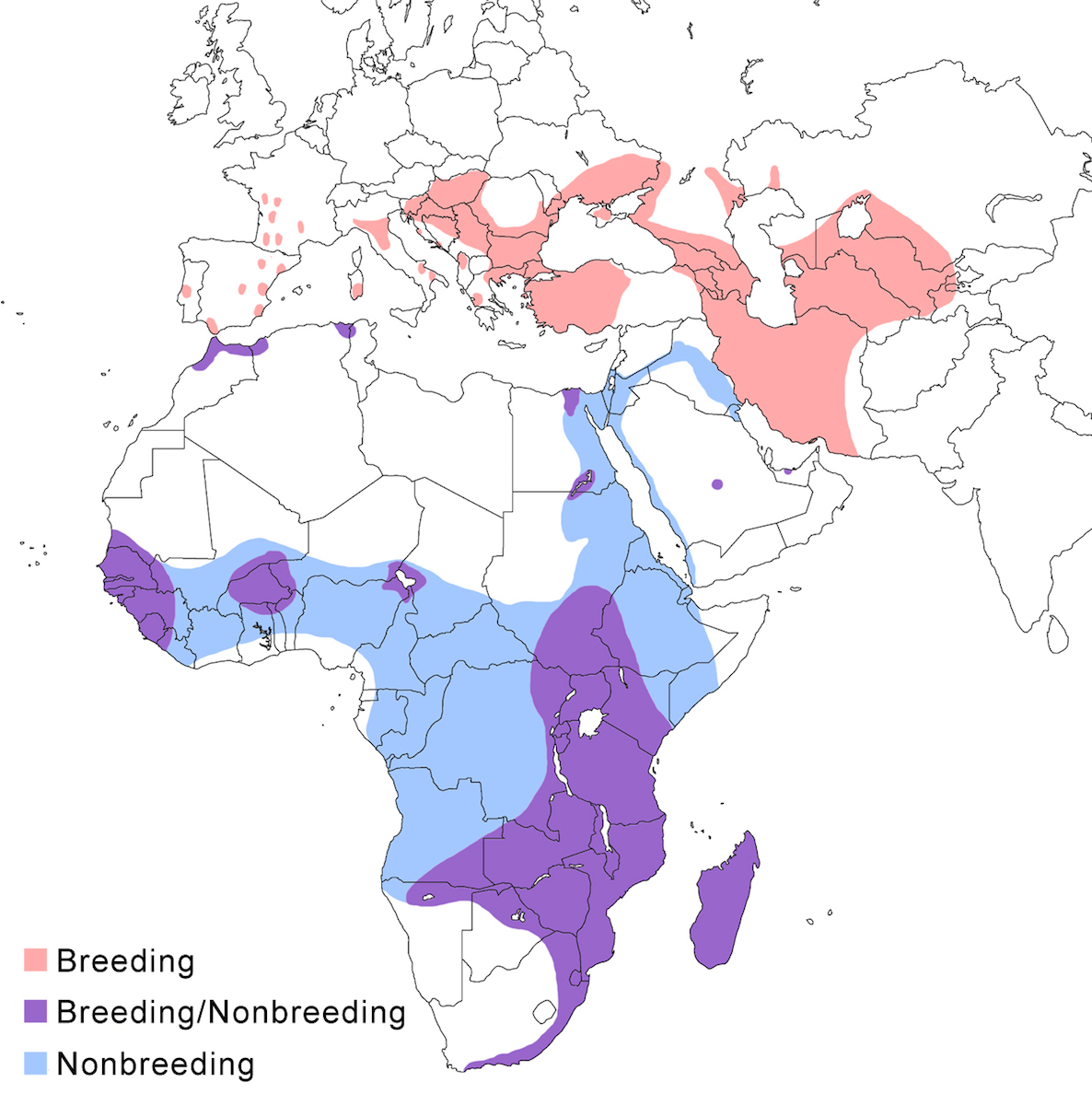

The Squacco Heron occurs in Europe, Africa, Madagascar, and the Middle East to Iran.

Breeding range: It breeds in scattered localities in Europe from south Spain, Portugal (Dias 1991), France (Loire Atlantique, Rhone Delta) (Caupenne 1993, Marion and Reeber 1997, Hafner et al. 2001), Italy (Fasola et al. 1981, Grussu 1987, Ciaccio and Siracusa 1989), Germany (Kolbe and Neumann 1990), Latvia, Hungary, Croatia, Albania, Greece, south Romania, Bulgaria (Delov 1993), central and south Ukraine, Moldova, Azerbaijan, south Russia, Kazakstan (Gordienko 1987), Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Iran, Saudi Arabia (James 1991).

In north Africa, it breeds in small numbers in Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia and also in Egypt on the Nile Delta and Answan (El Din 1992). In sub-Saharan Africa, it breeds over a wide area in Mauritania, Senegal, Gambia, Sierra Leone, Mali, Ghana, Nigeria, Chad, DR Congo, Sudan and Ethiopia, and from Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania south to Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Zambia, Angola, north Namibia, Botswana, and South Africa (to Cape Province) (Euston-Brown 1993), and over much of Madagascar.

Nonbreeding range: Northern populations winter in very small numbers in Spain, France and Italy (Kayser 1994, Hafner and Didner 1997) and in North Africa (Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Egypt). Most migrate further south into the Middle East, Iraq and Iran (Mesopotamian marshes), Oman, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates. The main wintering areas are in tropical sub-Saharan Africa, from Mauritania, Senegambia, Guinea-Bissau, Sierra Leone, Ghana, Nigeria, and Cameroon east to Rwanda, Uganda, Kenya and Tanzania. However, the southern limits of wintering northern birds are not clear because of overlap with local African populations.

Migration: Northern populations in Europe and west Asia are migratory. Southward migration is August–November, and appears to occur at a rather leisurely pace. Birds move in a broad front across Europe, the Middle East and the Sahara. Return migration is in February and March to as late as May. Migration appears to be along a broad front in that migrating birds are seen widely throughout the Mediterranean and its islands. Migration in both seasons crosses the Sahara.

Widespread post-breeding dispersal of juveniles begins in July continuing until migration. Spring migration leads to frequent overshoots. So, outlying dispersal records are common. Dispersal records include Iceland, Britain (Moon 1997, Greason 1998), Belgium, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Denmark, Germany, Sweden, Finland, Austria, Poland, west central Asia, Azores, Madeira, the Canary and Cape Verde Islands, and Brazil (Fernando de Noronha island) (Nacinovic and Teixeira 1989). In the Indian Ocean, there are dispersal records from the Comores and Mauritus, undoubtedly from Madagascar.

Status: Populations in Europe have fluctuated markedly (Marion et al. 2000). By the end of the 19th century populations had decreased due to plume hunting. They recovered but then declined again, attributed largely, often indirectly, to habitat destruction. For example between 1940-1960, the Western Palearctic population increased by 30%; but, between 1970 and 1990, two/thirds of the European breeding populations decreased by 20% or more (Marion et al. 2000). A more specific example is the history in the Volga Delta, where 7,000 pairs bred in 1970 decreased to an annual maximum of 300 in the 1990’s.

In recent years, the species has again shown population increases in south Europe - in Spain, Italy and south France. In the latter area, the increase has been extraordinary increasing from 105 nests in 1999, which was a number typical of the 1990’s, to 200 in 2001 (Hafner and Kaiser pers. comm.). The total European population is presently estimated to be 14,300-26,800 pairs, with the main concentrations being in Russia (35% of the European population), Turkey (32%), Bulgaria and Romania (Marion et al. 2000). Nesting sites are widely scattered in Europe and around the Mediterranean. Nesting numbers are in the low thousands at the most important sites, such as the Danube Delta, but nesting in west Europe is in the low to mid hundreds (Hafner 2000).

The species is rare in north Africa. It has recently been recorded as breeding in the Nile Delta (El Din 1993). Otherwise there were a few pairs nesting in Algeria and Tunisia and 15-85 in Morocco in the early 1980’s (Hafner and Didner 1997). Elsewhere in Africa, few data are available. It is a common and widespread species, although large colonies are well scattered (Hafner and Didner 1997, Turner 2000). Indications are that the species is increasing in range and abundance in Africa (Turner 2000), with the known breeding range increasing markedly in West Africa. In East Africa, the population in Tanzania may number up to 20,000 birds (Baker and Baker in prep.). Numbers in various breeding areas range from the hundreds to the low thousands. In Madagascar, the breeding population around Antananarivo has increased from 350+ pairs in 1969 to 1,000+ in 1990 (Langrand 1990, Turner 2000).

In addition to breeding birds, much of Africa supports nonbreeding birds from Eurasia. Year-to-year variation in the western European breeding population is suggested to correlate with rainfall on the wintering grounds in western Africa (Den Held 1981), although recent reanalysis shows weaker correlations (Fasola et al. 2000). Thousands winter in areas of West Africa, such as Guinea-Bissau.

Habitat

This species is a species that prefers dense, shallow, fresh marshes having nearby cover of tall reeds or dense bushes. It occurs usually in lowlands, river valleys, marshes, and estuaries. It can however nest to 2,000 m. The Squacco Heron particularly uses reed beds, marshes, rice fields, ponds, canals, ditches, irrigated land, and similar shallowly flooded areas. Seacoasts, reefs and islands are used on migration. Its principal habitat throughout its range is now rice fields, the extent of which is a likely cause for range increases. The species avoids both dry habitats and habitats with very high rainfall (Hafner and Didner 1997). For nesting, it tends to prefer dense trees and shrubs near its feeding areas.

Foraging

The Squacco Heron typically feeds by Standing very patiently and perfectly still, waiting for prey to approach. It also Walks, very slowly, searching for prey in a very Crouched posture, either in the open or among the reeds. It also uses Gleaning to take insects and snails off grass stems, Standing Flycatching, and Baiting (Prytherch 1980, Crous 1994). Feeding generally takes place among the vegetation at the edge of a pond or ditch. It also has been reported as feeding from branches over the water.

It usually feeds solitarily defending its feeding territory against other Squacco Herons using Forward displays and Supplanting Flights. More rarely it feeds in small groups of 2-5 birds, especially during the nesting season. It also feeds in large flocks in winter and on migration. Feeding success is higher for solitary birds than those feeding in flocks (Hafner et al. 1982). In mixed species groups it defends its territory but is also subjected to other interspecies interactions, such as prey robbing (Stival 1987).

It feeds during the day, but especially concentrates on crepuscular foraging, which can start an hour before sunrise and last until 90 minutes after sunset. It has been observed feeding at night. It appears to prefer to feed under cover, from the stems and branches of overhanging plants or wading in shallow water. However, it does feed in the open, especially in rice fields. It also feeds with cattle, like the Cattle Egret.

Although it feeds solitarily, it roosts in groups, using sheltered woods and less frequently reed beds. Roosting may continue at the colony site after nesting is completed. Roosts in nonbreeding season tend to be large, drawing birds from up to 80 km (Hafner and Didner 1997). Upon disturbance it assumes an Upright posture and may fly to another site.

The main diet consists of relatively small prey, particularly fish, frogs and tadpoles, and insects and insect larvae, dominance depending on place. Insects are most important in Russia, fish in Italy, frogs in France, a balance of insects, fish and frogs in Hungary (Molnar 1990). In rice fields it eats more insects than fish.

Insects include water bugs (Naucoris, Notonecta), water beetles (Dytiscus, Hydrophilus, Cybister, Hydrous), grasshoppers, crickets, mayfly larvae, dragonfly larvae (Libellula, Aeshna), and fly larvae. Amphibians include frogs and their tadpoles (Rana, Hyla, Bombina). Fish include Scardinus, Cyprinus, Carassius, Rhodeus, Alburnus, Lipomis, Tinca, Leiciscus, Abramis, Anguilla, the introduced Gambusa and Lepomis. Other prey include amphipods (Gammarus, Apus), crustaceans, spiders, snails, earth worms (Lumbricus), lizards (Lacerta), snakes (Natrix), and mammals (Sorex). It can eat rather large prey, including fish to 10 cm and small birds (Sylvia, Anthus) (Gordon 1986), and will attempt to eat even larger prey, such as a Wood Sandpiper (Tringa) (Van der Ham 1984).

Breeding

Herons in Europe nest from late April to late July, stretching from mid April to August in Spain. In North Africa, egg laying is April–June. In Africa, breeding generally takes place during or at the end of the rainy season, the latter particularly the case in inundation areas, though there are many West African records of nesting in the dry season. In southern Africa, breeding has been recorded throughout the year, particularly in years when the summer (November–December) rains are far above average. In Madagascar, breeding takes place from October–March, peaking in November–December.

This species nests in dense bushes or small trees, (although sometimes to 20 m), near or overhanging water. It also nests less frequently in reed beds and papyrus swamps, using either the reed or small trees.

The Squacco Heron typically nests colonially with other species, in small or sometimes large mixed colonies, including cormorants (Phalacrocorax), ibis (Pleagadis), and other herons, especially Little Egrets, Black Crowned Night-Herons, and notably the Malagasy Pond-Heron in Madagascar. In colonies, nests tend to be distant, 5-10 m apart, but may be as close as 0.5 m. Nesting colonies occur within proximity to feeding areas, generally within 5 km. It also nests solitarily.

Nests are small, bulky and compact, 17–27 cm in diameter, either flimsy or substantial, up to 20 cm deep, made of reeds, grass and sometimes twigs. They are built low to the water from almost on the ground to 1.5 m in reeds, papyrus, or low trees. In some colonies they are at the intermediate heights, above ground nesters but below the canopy nesters (Fasola and Alieri 1992b). The nests are built by both sexes, usually with the male bringing the sticks, though building by each sex alone has been reported. The nest structure can be completed in 6-8 days, but material is added later as well.

The male builds a platform from which to advertise. It defends its advertising site and a larger area with Forward displays. The Squacco Heron’s Forward is given with legs bent, bill aiming at the opponent, folded wings slightly aside, in crouched posture, neck bent back, all plumes fully erected nearly doubling the bird’s apparent size. The Squawk call is given. The heron also uses an Upright display with all feathers sleeked. It is often a prelude to a Forward. When alarmed, it gives its Grrr call, which is commonly heard in a colony.

The Stretch display (also has been called Foot Lifting in this species) is the principal courtship display (Voisin 1991). The heron perches on a branch, with feet apart, bends slightly, grasping the branch tightly with one foot while loosening the grip on the other foot, which it lifts and extends, then alternates with the other foot. At the same time as it sways from side to side, it stretches its neck downward.

Copulation occurs on or near the nest site. Upon pairing, contact Bill Clappering and Back Biting are common. In the Greeting Display, the approaching bird fully erects its plumes. The receiving bird does the same. As they meet they mutually do a Forward display, which is soon dissipated (Voisin 1991). The male often brings a stick.

Eggs are green blue. They average 39 x 28 mm in Europe, 38 x 29 in southern Africa, and 37.3 x 27.5 in Madagascar. The clutch is 4-6 eggs in Europe but only 2-4 in Africa and Madagascar. Clutch sizes have decreased in south Europe (Camargue) over several decades (Hafner et al. 2001). Eggs are laid at one to two day intervals. Incubation begins before completion of the clutch, likely after the second egg. Incubation is 22-24 days in Europe but is reported to be only 18 days in Madagascar (Milon et al. 1973). Incubation appears to be mostly by the female. Eggs hatch at 1-2 day intervals.

Chicks are fed by both parents, at first by regurgitation and then by food deposited at the nest. Later the chicks rundown the parent and grab the adult’s bill. Young begin to clamber from the nest into branches at 14 days. They can fly at 30 days, fledged at 45 days. Young form groups at the colony site. They become independent soon after 45 days. In the Camargue, 79.2% of eggs produced young (Hafner 1978). The average brood size is 3.2-3.3 (Hafner and Didner 1997). Lost of eggs and nestlings include predation by hawks (Accipiter) (Kayser 1995).

Population dynamics

Generally they breed at two years, but one banded bird was observed to breed at one year. Little is published about the long-term demography of the species.

Conservation

The greatest conservation issue is the protection and restoration of habitat for this species (van Dijk and Ledant 1983, Pyrovetsi and Crivelli 1988, Fernandez-Cruz et al. 1993, Hafner 2000). It is likely that habitat degradation has been the cause of various population declines. The species’ adoption of rice fields has been responsible for range and population increases, where they are occurring. Both natural and artificial habitats are under threat. Rice field suitability depends on cultivation practices, which affect prey availability (Hafner and Didner 1997). The species also depends on wooded sites near feeding areas for nesting, and these too are under threat. Conservation should be focused on protection and management of appropriate feeding and breeding habitats.

Research needs

The Squacco Heron is a well-studied species. Perhaps the most important further work is that linking populations and nesting success to habitat features. This information is needed in order to design habitat conservation strategies and to better understand the role of habitat in population fluctuations. The comparative biology of temperate and tropical populations could provide interesting insights into the relative roles of breeding and non-breeding ecological conditions in the life history and demography of the species. The evolutionary relationships of the several pond herons require additional study to determine their most appropriate classification. The four species making up the ralloides group of pond herons are closely related, generally allopatric forms, differing mostly in plumage characteristics. The situation is analogous to Butorides. Study using molecular techniques should be conducted to determine the species limits of this group of birds.

Overview

The Squacco Heron is a brownish-buff bird that blends completely into its surroundings. It typically is a lone feeder, standing, crouched low and still, watching for prey in the water below. It is bird of dense marshes and rice fields. The alarm and flight call is highly recognizable, giving the bird its name. Populations fluctuate, the causes not being clear; hunting, habitat change, and perhaps climate have all been advocated. The increase in rice fields are a likely cause of its recent population growth. Northern populations are highly migratory, and so may be affected by conditions in sub-Saharan Africa. Population fluctuations and shifts seem an integral aspect of the biology of this widespread and successful species.