White-necked Heron

Ardea pacifica (Latham)

Ardea pacifica Latham, 180 1. Ind. Orn., Suppl. 1, p. 45: New South Wales.

Other names: Pacific Heron, Crane in English; Garza de cuello blanco in Spanish; Héron à tété blanche in French; Weißhalsreiher in German.

Description

The White-necked Heron is a medium to large, robust looking, grey heron with a completely white neck and head.

Adult: The head and neck are white, with black spotting running vertically down the foreneck. The irises are yellow to green; lores are dark grey to black, often with a cream green to pale yellow streak from the bill to the eye. The bill is black. The upper parts of this heron are sooty to dark grey. The upper wings are dark slate grey, with a white “shoulder” patch visible in flight. The under parts are dark slate grey with white streaking. The legs are black, but it can have a yellow olive tinge on the lower leg.

During breeding plumage the heron tends to become darker, a dark grey to black on back, tail and upper wing with greenish sheen. The head and neck are white, but the dark spotting on the throat may be more chestnut colored. Bill is black and the irises are yellow to green. The lores become blue during courtship. Maroon lanceolate plumes develop at the base of the foreneck and along the back. The characteristic white patch on the wings becomes more prominent. The under parts are streaked with white. Legs are black.

Variation: The sexes are alike, but females average smaller than males. There is considerable variation in size among individuals, up to 30% in length.

Juvenile: Immature birds have grey to buff white heads and necks and lack plumes. Their lower bill is yellow to white. Irises are dark brown to bronze.

Chick: Downy chicks are grey white, with whiter head and neck apparent.

Voice: This heron is characteristically a quiet bird, at least away from the nest site. It issues a hoarse guttural croaking alarm call when disturbed. At nest adults make guttural noises. The “Oomph” call is given during Stretch and Wing Touch. Cackles are made during the Greeting Ceremony. Chicks give a rasping call to contact parents. Additional information is needed on the vocalizations of this species.

Weights and measurements: Length: 76-107 cm. Weight: 650-860 g.

Field characters

At all ages and stages this is an unmistakable heron, with its contrasting white neck and head and its grey body. It is identified by the combination of medium size, dark plumage, and white neck and head color. The White-necked Heron flies with slow wing beats with head drawn back, looking heavy and large. In flight the white patch is highly visible on the leading edge of the otherwise dark wing and is a good field character.

It is distinguished from the White Faced Heron by its all white head. It is distinguished from adult Pied Herons by its larger size, white (not black) head, white neck with prominent ventral spotting, dark (not yellow) bill, and dark (not yellow) legs. Pied Herons, however, are variable and can have very white heads, but generally with less spotting and always with light rather than black legs and bills. The White-necked Heron can be confused with juvenile Pied Herons that have a white head and light to white underparts. It is distinguished by its larger size, neck spotting, dark bill and legs, and solitary (not highly aggregative) behavior.

Systematics

This species is related to the other medium to large Ardea herons, but remains to be understood about the interspecific relationships among these herons.

Two English names are widely used. We suggest the name “White-necked Heron” as being descriptive whereas “Pacific Heron” is derived from its scientific name and is a poor description of its range. This name is also appropriate for the Cocoi Heron, but the Cocoi Heron’s predominant characteristic is its black head whereas the predominant characteristic of pacifica is the white neck and head.

Range and status

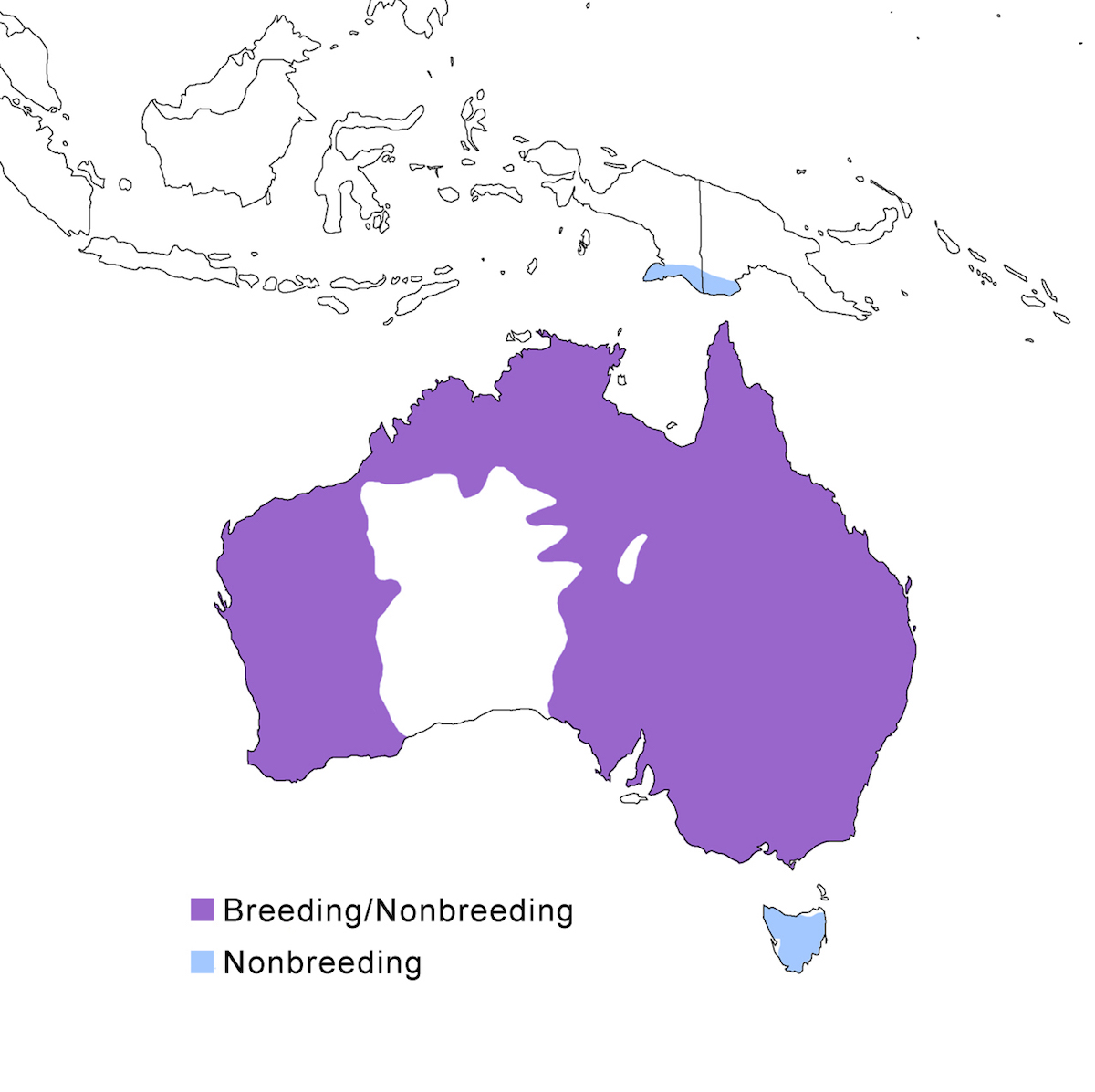

The White-necked Heron is endemic to Australia.

Breeding range: The species has bred throughout much of Australia outside of the deserts. Although some colony sites are permanently occupied, this is an eruptive, nomadic species that can locate suitable feeding conditions and nest as conditions allow. Consequently its exact nesting range is highly flexible, including Tasmania. It has expanded its range in northwestern Australia in the past fifty years.

Nonbreeding range: As a nomadic species, it can turn up almost anywhere outside the nesting season, occupying a site for as briefly as a few days. It is regularly reported in New Guinea (Transfly, Port Mosby, and elsewhere), Tasmania, and Bass Straits Islands.

Migration: This is a mobile heron that undertakes both regular migrations and event-triggered dispersal. Migrations occur between breeding sites and seasonally suitable wetland feeding habitats. For example, inland from Darwin, herons nest from June to August and then most migrate away for January to May. Conversely they appear in the north of Australia during the nonbreeding dry season (Morton et al. 1993). Irruptions occur when especially favorable feeding conditions occur and the herons move to use them (Dell 1985). The eruptive tendency of this species results in dispersal records occur elsewhere in the nearby Pacific, for example New Zealand, much of New Guinea, Norfolk Island, and Tristan da Cunha.

Status: This is an uncommon species but one that is wide spread. All signs are that the Australian population is stable. It is uncommon in Tasmania and New Guinea and a vagrant in Zealand.

Habitat

The White-necked Heron uses a variety of inland wetlands, grasslands, and permanent and temporary water bodies freshwater swamps, lagoons, billabongs (waterholes), and river floodplains. It also uses reservoirs, dams and roadside ditches. The heron most often chooses very shallow water sites having a depth of than 7 cm, usually in marsh or wet grass where there is a clear view of its surroundings.

Foraging

The White-necked Heron typically feeds alone or in pairs in wet grasslands and shallowly flooded marshes and other shallow site. The species will defend its feeding site from incursions. At sites of abundant prey, it sometimes feeds in small dispersed groups or in flocks up to several hundred. It feeds mostly by Standing and also by Walking Slowly from both Upright and Crouched posture traveling slowly along the margins of swamps, wet pasture, or along the water’s edge. Its feeding rate is less than a stab a minute. It also uses Foot Raking, Diving into the water from overhanging limbs, and Hovering (Ley 1991) and will steal food from ibises and raptors.

Diet is versatile and broad, depending on availability. Food is typically small aquatic prey, tending to be less than 3 cm long, although a prey item over 10 cm long has been recorded (Recher et al. 1983). Its diet primarily includes frogs and tadpoles, newts, lizards, mussels, shrimp, crayfish, insects such as dragonfly larvae, mantids, grasshoppers, beetles and beetle larvae, fish, small birds and mammals. Although it eats fish less than other herons, it does include them in the diet when available (Ley 1991). Under appropriate conditions it will eat carrion.

Breeding

Nesting season is flexible, generally during the rains and in wet years can be year round. Nesting season is typically in the spring and summer in the south and Tasmania, September to February and sometimes into April. Nesting in the north is December to March.

They nest freshwater swamps, marshes and grasslands, especially areas that remain flooded for several months or permanently (Briggs et al. 1997). Within this habitat, they use in tall trees, often dead, as high as 40 m, near of over standing water, and convenient to feeding areas. This heron is colonial, nesting in small, dispersed colonies of 2 to 30 nests, but also up to hundreds. They nest also in mixed colonies of other herons, ibis (Threskiornis), spoonbills (Platalea) and cormorants (Phalacrocorax). Compact nesting is possible with up to five nests have been observed in a single tree. Solitary nesting occurs such as at small water bodies, but contrary to some literature, this is not typical of the species

Nests are loosely constructed stick platforms 30-60 cm across. Nests can be reused in successive years. Twigs collected by males near nest sties, from other nests, or even in flight from the water.

Some aspects of nesting behavior are described (McCouloch 1976, Marchant 1988, Lowe 1989, Marchant and Higgins 1990). Solitary males select and attend future nest sites, standing on or near it for long periods preening or displaying. Birds fly out in Circle Flights, without calling, but with deep wing beats and neck extended (McCulloch 1967). When occupying a potential nest site, the displaying male gives Wing Touch and Stretch displays, often repeated between bouts of Preening and Standing. The Stretch includes an “oomph” call. Both birds occupy the nest site, Preening and Standing. Body Shake and Twig Shake displays are given. May use mutual Circle Flights that includes hovering and swooping toward each other, however this has been considered and adult-young interaction (Marchant and Higgins 1990). After pair formation, nest exchange Greeting Ceremony consists of Upright display with raucous cackles.

The White-necked Heron also appears to perform display rituals away from the nesting sites. The bird has been observed repeatedly and gently doing the Stretch, followed by a bobbing downwards of the legs, in a tree standing in water at a location well isolated from any known nesting site. The action was by far less vigorous than the equivalent usual display of the Eastern Great Egret (M. Maddock pers. comm.).

Eggs are pale green blue, slightly pitted, and average 58 x 39 mm.Clutch is 4 eggs, occasionally 2-6. Incubation is 28-30 days. Both adults feed young by regurgitation. Young give rasping calls in the nest. Parents continuously attend and guard nest and small young until 3-4 weeks. Older siblings harass smallest chick, which usually dies. Generally two chicks are produced. Fledging occurs in 6 to 7 weeks. In colonies, young form groups on branches.

Population dynamics

Little is known of the population dynamics of this species.

Conservation

As a widespread, adaptable, and still common bird in Australia, its population is considered to be stable and is not of immediate conservation concern. Its expansion into northwest Australia was due to its ability to exploit irrigation and reservoir development. However, this Australian endemic depends, for nesting on inland seasonal wetlands, which have been under threat for decades. Artificial wetlands and other aquatic sites can be managed to support herons by water control and maintenance of nesting trees (Briggs et al. 1997).

Research needs

Much additional study is needed to fill gaps in the basic biology of this species, particularly the movements of individuals and populations within Australia, and the relation of hydrologic conditions to breeding success, demographics, and population biology.

Overview

The White-necked Heron is an excellent example of a nomadic heron. It is highly mobile, moving around in response to seasonally and annually varying rainfall patterns that typify much of the Australian continent. The resulting flooding provides ephemeral food supplies. Finding and exploiting temporary hydrologic conditions are keys to this species’ ecology and life history. Where conditions are stable, it breeds in successive years. In the comparatively reliable rainfall areas of eastern and southeastern Australia, fairly stable groups of 20–30 may congregate to nest and remain indefinitely. Possibly these are the small resident populations from which nomadic individuals radiate during droughts. Such movements result in distant dispersals. Its nomadism sets this species apart from many other medium to large herons. As a result of its versatility, its diet is broad. It can feed, nest, or roost alone or in groups. It can expand and contract its distribution as conditions dictate, finding and exploiting available food supplies for feeding and breeding. It is a species well adapted to the harsh climatic conditions of the Australian continent.